Building the Impossible: Engineering’s Hidden High Performers

Designing iconic buildings means balancing ambitious designs with the growing need for resilience, longevity and sustainability. How can architects and suppliers work together to expand the boundaries of what’s possible?

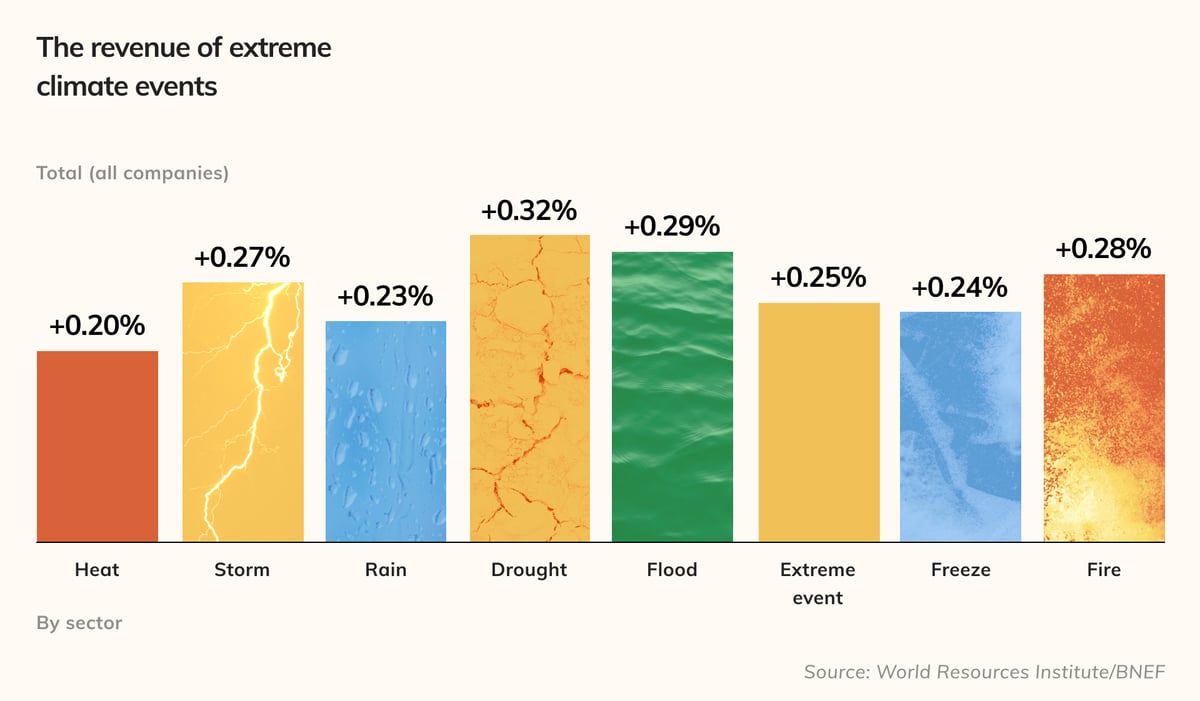

From floods to wildfires, the impact of extreme climate events on revenue can be significant. Research by BloombergNEF indicates that companies experience an average revenue loss of 0.3% for each climate-related weather event. For the construction industry, the research notes that storms and flooding are among the most prominent risks.

The uncertainties of climate change only add to the challenge. In February 2024, the EU’s Climate Change Service found that for the first time, global warming exceeded 1.5C above the pre-industrial average for the previous year.

In practice, many architecture and engineering firms do not consider climate projection data in their design decisions, yet it’s clear that property developers and owners are increasingly trying to protect their revenue base by implementing solutions for a sustainable future that mitigate the impacts of extreme weather.

“Space and material are precious and must be used wisely and sensitively to ensure that we create buildings not only for today, but for future generations,” explains architect Ole Scheeren, principal of Büro Ole Scheeren, one of the world’s leading architects.

So what does this mean for iconic building projects with increasingly ambitious architectural designs? And how can firms reconcile aesthetic demands with the need for resilience, longevity and sustainability?

Future-proofing visionary projects

Landmark buildings need to stand out. But iconic structures are also defined by the feats of complex engineering needed to fulfill both aesthetic and practical ambitions. Future-proofing these structures against physical risks requires solutions that are both sophisticated and sustainable.

In London, “The Gherkin” is a building that responds uniquely to the constraints of its site in the city’s financial district, and it is among the most recognized silhouettes in 21st-century architecture. Designed by Foster + Partners, the building’s finishing, sealing and bonding materials were supplied by global chemicals and engineering leader Sika. The Gherkin’s glazing adhesive and weatherproof sealing ensures that the building’s distinctive triangular glazing will stand the test of time.

As well as restoring historic structures, including the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Sika also deploys its expertise to future-proof newer projects in challenging climates.

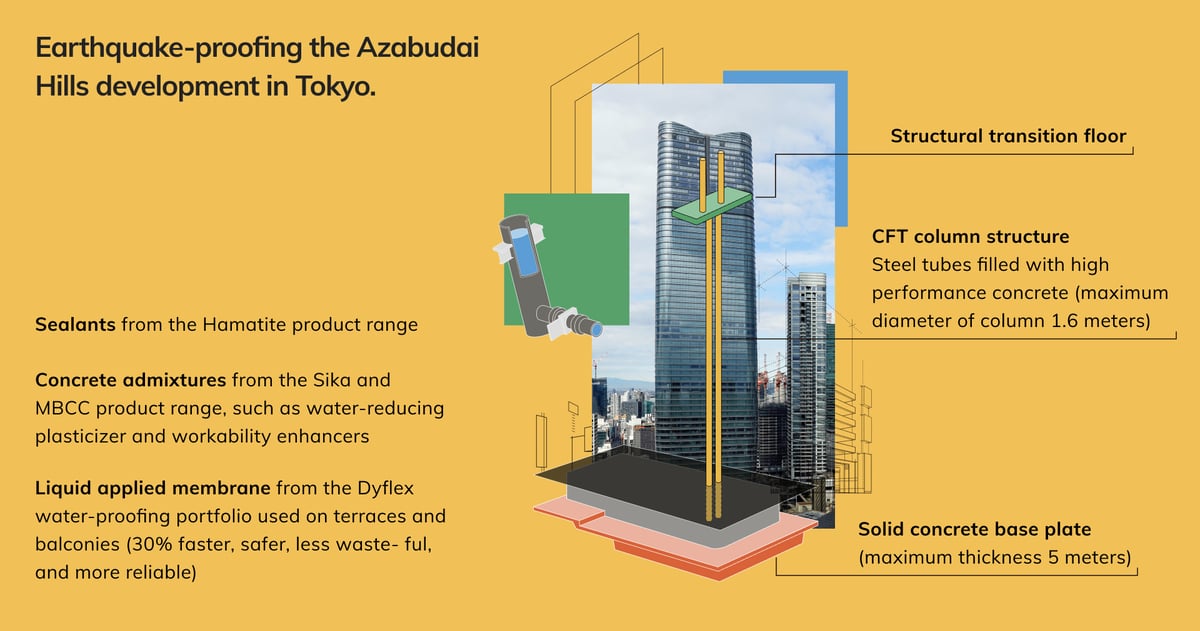

Japan, which is hit by hundreds of earthquakes each year, maintains rigorous building standards that require high levels of reinforced steel in concrete. When it came to fortifying the striking Azabudai Hills development in Tokyo’s Minato district, earthquake-proofing was front and center. Based on a vertical garden city concept, the development provides earthquake shelter not only for its residents, but also for an additional 3,600 people.

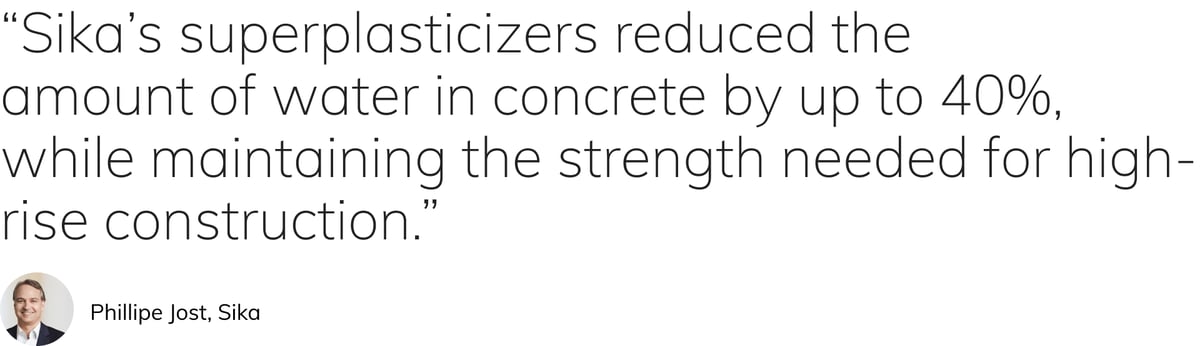

Strict specifications for earthquake resilience, together with a tight building schedule, meant that the concrete needed to be highly flowable for several hours, while also developing high strength rapidly—goals that seem contradictory. But its development of novel polycarboxylate-based admixtures meant that Sika was able to meet these stringent requirements. In fact, all of Tokyo’s buildings higher than 187 meters – 53 buildings in total – were built with Sika technology.

From waterproofing to water reduction

Resilience against extreme weather events is critical in Thailand. The country’s monsoon season, typically between June and October, often sees major flooding—a key consideration when embarking on ambitious design projects like the Mahanakhon tower (King Power Mahanakhon) in Bangkok.

Designed by Scheeren and opened in 2016, Mahanakhon is an ultra-modern skyscraper with a fragmented design reminiscent of a Jenga tower. The building’s SkyWalk observation deck offers panoramic views from 314 meters above the city.

"Space and materials are precious and must be used wisely and sensitively to ensure that we create buildings not only for today, but for future generations,” explains architect Ole Scheeren, principal of Büro Ole Scheeren, one of the world’s leading architectural firms.

Mahanakhon includes sustainable features, such as energy- and water-saving materials and systems.

Pushing the limits

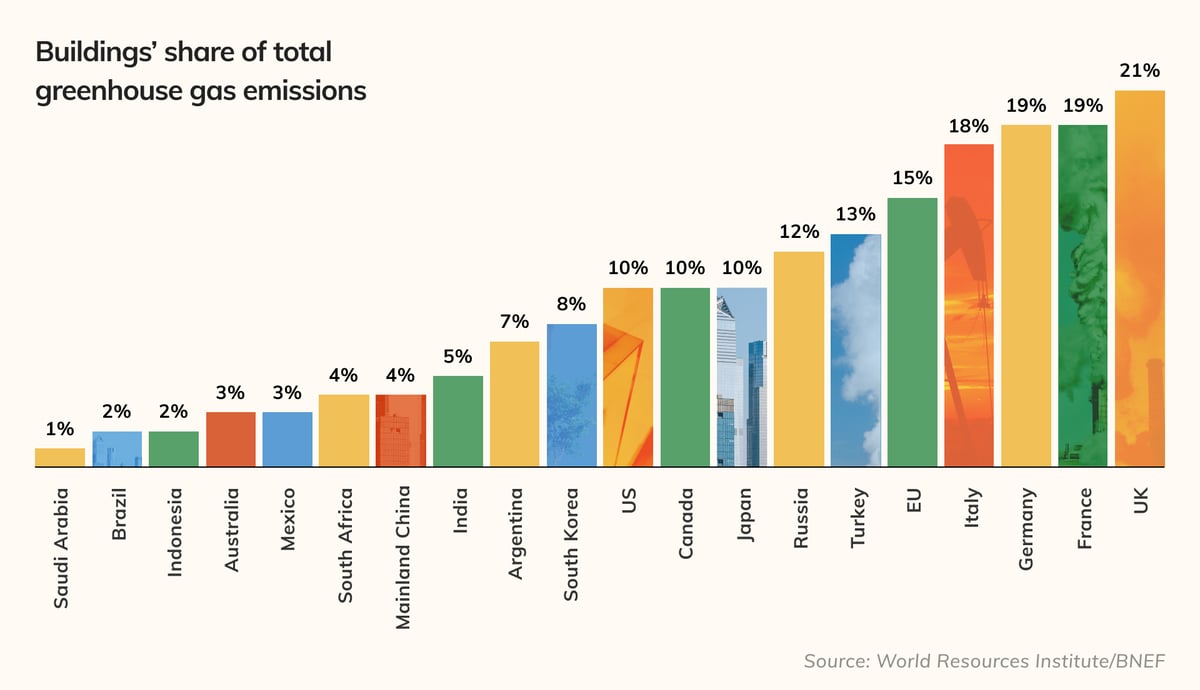

For the construction industry, the drive toward sustainability and decarbonization presents a major challenge. Reducing the carbon footprint of a structure requires looking not only at the materials used, but also at the design of the structure and the energy needed to heat or cool the building.

Modern buildings also need to be designed with an eye to the end of life. “This means that a building will be designed and built so that it can be disassembled, and the materials can be reused,” says Phillipe Jost, Regional Manager Asia/Pacific at Sika. “This is only possible with cooperation between designers, suppliers and, of course, regulators that allow or even incentivize the use of novel technologies.”

The sector’s efforts to tackle these challenges aim to improve liveability in major cities, as well as address the risk of extreme weather events. For example, taller buildings can enable more recreational space by increasing density, while effective wastewater and freshwater management can reduce both pollution and flooding.

As extreme weather continues to affect the design agenda of complex projects, innovative solutions will play an increasingly important role in stemming the revenue loss brought about by physical risks. Jost believes that pushing the limits, and developing new materials and construction methods, will allow the city of the future to become more attractive, “not only for working, but also for living.”

For Scheeren, building for the future—and for the well-being of humans—is not only a technological challenge, but also a social and psychological one. “We must use the technologies available to us to create true ‘spaces of life’—a quality that captures the sum of experiences, emotions and memories of people in a living and breathing ecosystem,” he says.