How to Integrate the Impact of Climate Change into Strategic Asset Allocation

Along with environmental and biological impacts, the resultant economic threat from climate change is profound. Today, fund management companies face the challenge of integrating climate change projections to the assess risk and return expectations that inform their investment strategies.

Fidelity International, for instance, has been assessing the impact of climate change, the responses by global policy makers and how various climate risks may affect capital markets. It recently published its findings in the report Planetary risk: mapping climate pathways to macro and strategic asset allocation.Setting a framework around uncertainty

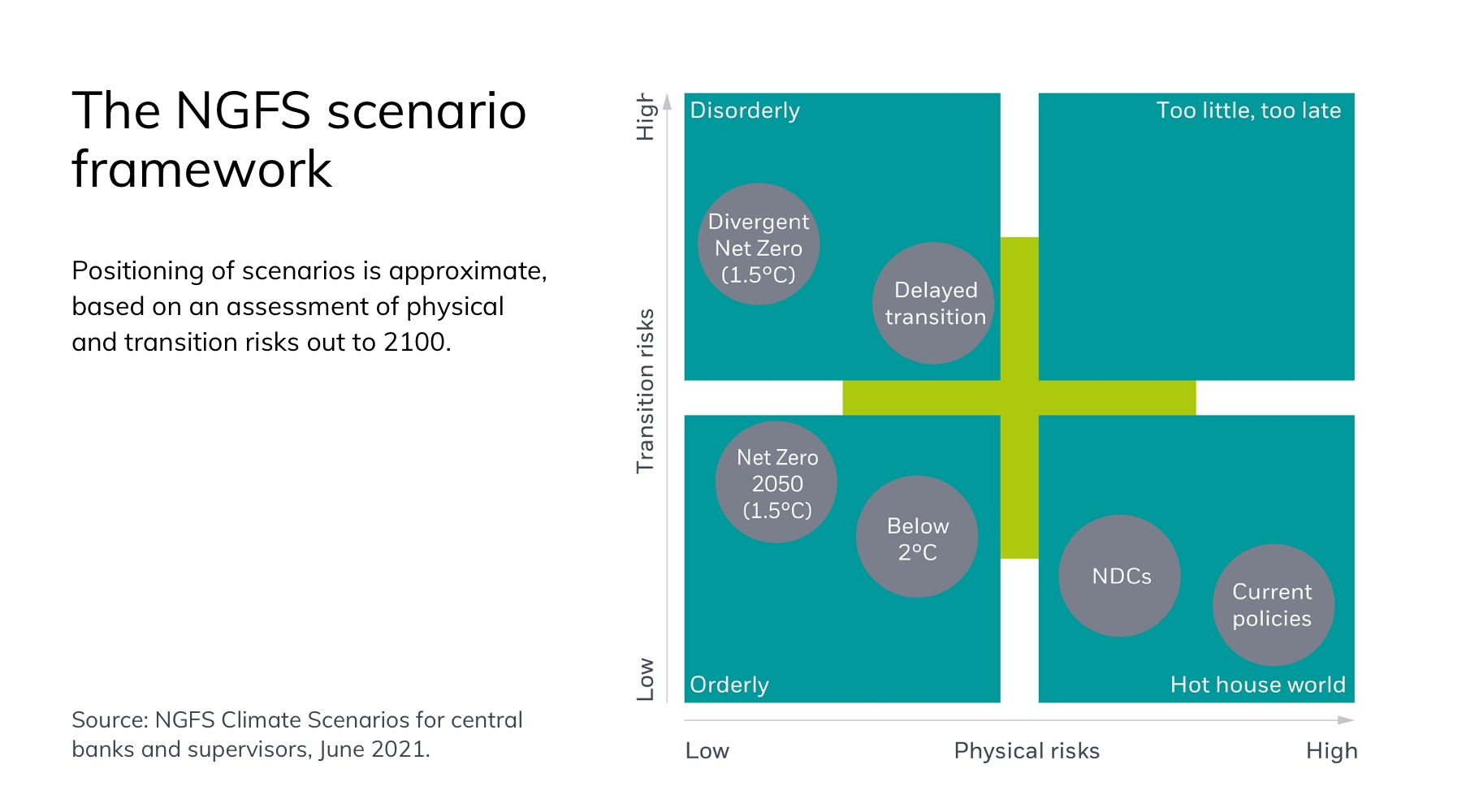

The framework underpinning Fidelity’s strategic asset allocation process is one collated by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS)—a collective of central banks and financial supervisors that develops environmental and climate-focused risk management to move the financial system toward supporting a sustainable global economy.

Operating with “the science of uncertainty” is far more feasible with a framework in place, according to Salman Ahmed, Fidelity’s Global Head of Macro and Strategic Asset Allocation.

Focusing on transparency and disclosure, risk management and the mobilization of capital and investment opportunities, the NGFS presents a coordinated financial framework to support the global effort to meet the climate goals of the Paris Agreement. The framework has developed a series of scenarios—ranging from lower- to higher-risk outcomes—that provide policy makers with a common starting point for analyzing climate risk to the economy and financial system. The People’s Bank of China, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England are already using the NGFS scenario set to undertake a variety of stress tests, which formally incorporate the role of climate change in assessing financial and economic risks over different time horizons.

These scenarios are deemed “Orderly,” defined by early and ambitious action taken toward a net zero carbon economy by 2030; “Disorderly,” where action is late, sudden or unexpected; and “Hothouse World,” in which action is limited, leading to significant global warming and heightened physical risk to the planet.

Fidelity is incorporating these climate change pathways into its long-term capital market assumptions (CMAs), which inform its strategic asset allocation decisions and, ultimately, its overall investment strategy.

According to its report, Fidelity believes that mainstream long-term macroeconomic projections, and consequently consensus CMAs used by the investment industry, “underplay both the magnitude and geographical dispersion of climate change impacts on key macroeconomic variables such growth and inflation.”

Assessing physical and transition risks

Ahmed’s team considers the implications of current conclusions emanating from climate science in two aspects: transition risk and physical risk. Transition risks relate to policy and regulation, technological development, and change in consumer and corporate behaviors. Physical risks can either be chronic, such as rising temperatures, precipitation and sea levels, or acute, involving extreme—and increasingly common—events such as heat waves, wildfires and cyclones. These are then mapped to macroeconomic variables to determine the implications for GDP and inflation across a spectrum of expectations, from conservative to aggressive.

The inflation argument spans both these perspectives. “If the physical threat of climate change becomes increasingly serious after 2050, we can foresee a supply-side shock, driven by the physical manifestation of climate change in the very long term,” Ahmed says.

Transition risk sits largely in the hands of governments. “If the world takes credible action now to mitigate climate change, in some form or another we will have to introduce carbon taxes into the system—either directly or indirectly—and the impact of such policy shifts will be felt now, not in 2050,” he says.

“If mitigation means that policy has to change, and corporate behavior has to change, household behavior has to change. The overarching term is ‘transition risk,’ and if carbon taxes are seen as part of the solution, it will cause a meaningful inflationary shock for a number of advanced and developing countries.”

Much of this inflation risk comes from the rising price of carbon offsets; the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has forecast a rise from $2 per ton of carbon to $75 per ton by 2030 if signatories adhere to the Paris accord. Applying a carbon tax will ultimately drive consumer price inflation (CPI) upward, which could be partially offset by other policies, such as green subsidies or infrastructure investment.

“A company emitting CO2 free of cost enjoys the benefit, while the whole planet pays the price.”

— Salman Ahmed, Global Head of Macro and Strategic Asset Allocation, Fidelity

Essentially, if carbon is priced at a level that takes the resultant climate damage into account, electricity and other input prices are expected to rise. “Economists refer to this as correcting an ‘externality,’ where the cost is public and the benefit private,” explains Ahmed. “A company emitting CO2 free of cost enjoys the benefit, because the cost of producing their products goes up but they can pass it on to their customers—while the whole planet pays the price.”

Ahmed also points out, according to the current understanding based on climate science, geographical differences, with the tropics and Southern Hemisphere—comprising many emerging markets—demonstrating far more vulnerability than the Northern Hemisphere if the climate goals of the Paris Agreement are not met.

The change in GDP per capita due to climate change shows a distinct North-South divide. Canada, the U.K., Northern Europe, Russia and the Baltic states look set for a significant increase in their growth prospects, whereas most countries on or below the Equator are expected to see a large decrease in GDP. While the data indicates extreme variation in climate impact, the net GDP loss to the entire world is increasingly significant, and there is at least a 50% chance that climate change will shrink total global GDP by more than 20% by 2100 if substantial action is not taken[1].

Even these alarming estimates are conservative and fail to account for flooding risk in the U.K. and Europe, for example, or Scandinavian countries being affected by changes in the Gulf Stream. “But even with this conservative impact assessment, you can expect significant impact to your return projections under scenarios where no action is taken to reduce GHG emissions,” says Ahmed. “This is just one example of how we try to manifest such uncertainty into numbers and therefore understand the calibration of risk and expected returns stemming from our capital market assumptions building process.”

These frameworks, grounded in scientific evidence, help investment groups such as Fidelity understand how potential outcomes, and different states of the world when it comes to climate change, will affect inflation, GDP, default risk and other factors such as insurance premiums. Modeling these elements under various response scenarios, while determining CO2 emission variations and the impact on industry sectors, forms a basis for long-term asset allocation strategy.

Against such an uncertain future, the only certainty is that climate change risk is not going away, so the more prepared investors can be for its impact, the better. According to Fidelity, while a number of factors putting pressure on inflation currently are likely to be transitory, “we believe policies to achieve net zero by 2050 have the potential to bring out more persistent inflationary forces which are still not discounted by the markets and are underestimated by investors.”

Source

- Stanford University, Fidelity International