How AI Is Helping Communities Anticipate Floods

In early July—just a month into India’s 2023 monsoon season—the north of the country endured an onslaught. Himachal Pradesh, where residents already face the ups and downs of mountainous terrain that clings to the Himalayas, saw its heaviest rainfall in half a century. Meanwhile, due south in Delhi, 15% of the total rainfall the region expected from June to September fell in just 12 hours.

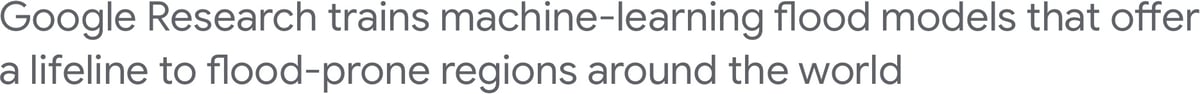

Events like these, which are increasingly common due to the changing climate, are raising alarms in India, the world’s most populous country, which experiences 20% of the world’s flood-related fatalities.

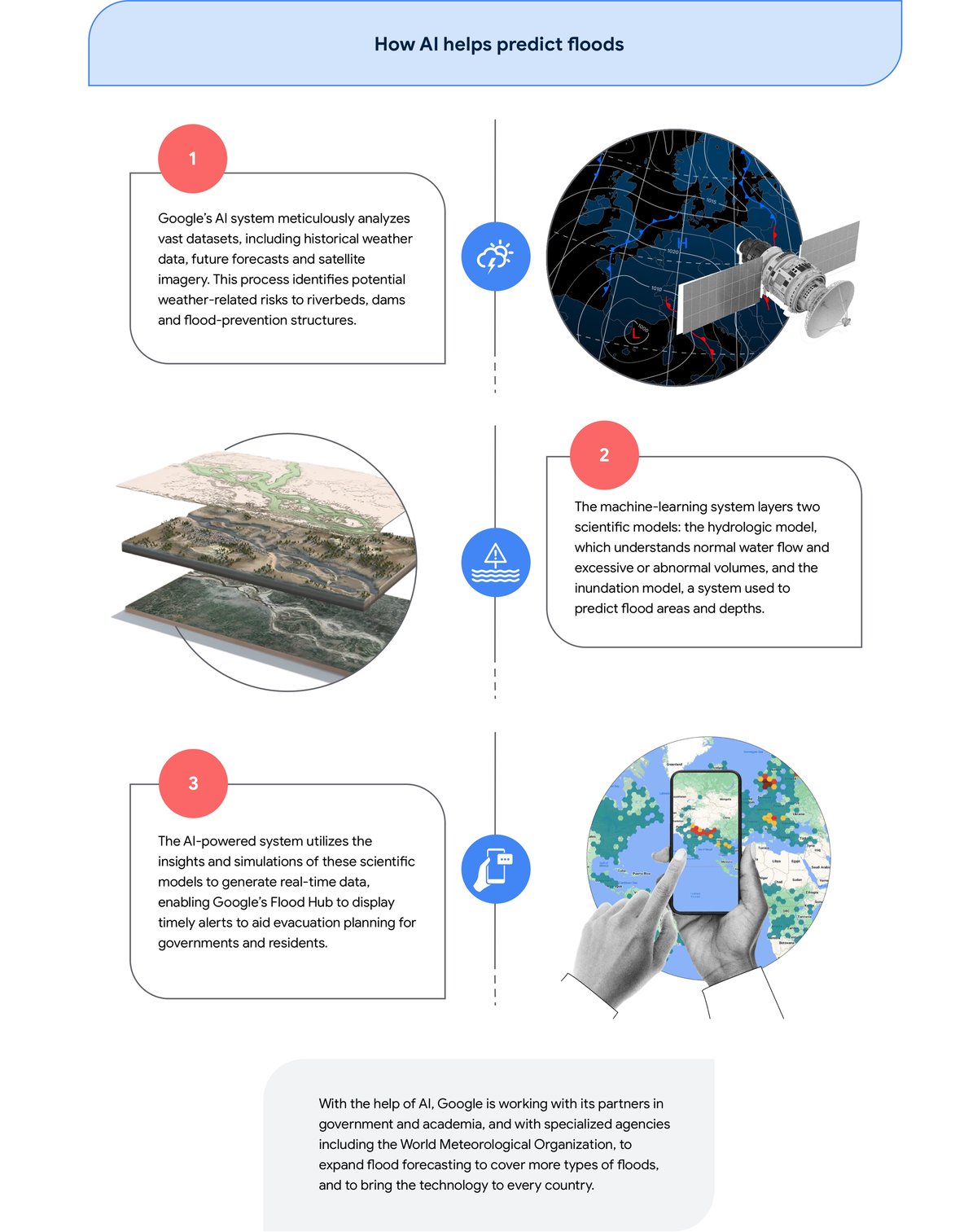

The scale of this human cost is why Google chose India and neighboring Bangladesh to begin an ambitious AI-powered flood forecasting initiative in 2018, using weather data, spatial mapping and predictive modeling to train a neural network to generate and issue flood warnings with longer lead times than had previously been achievable.

In 2022, Google launched the Flood Hub, aimed at providing useful flood information to people, governments and aid organizations worldwide so they can take appropriate action.

Flood Hub is now available in more than 80 countries, and in many countries flood forecasting alerts are also accessible through Google products like Search and Maps, reaching people in flood-prone areas.

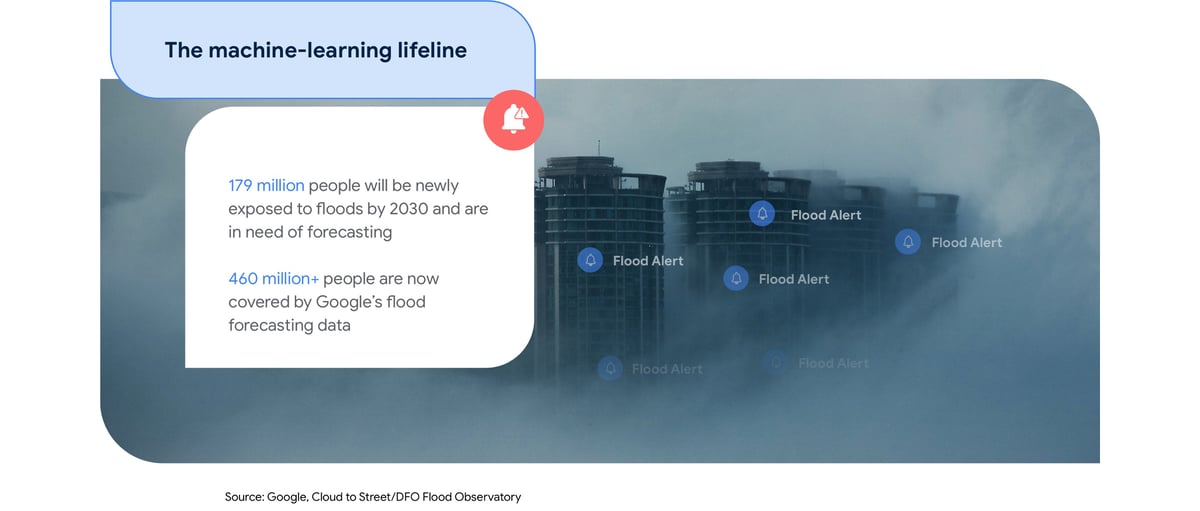

This system delivers comprehensive Flood Hub data and forecasts to 460 million people up to seven days ahead of potential riverine flooding events, supporting the World Meteorological Organization's efforts to ensure everyone around the world receives early warnings for climate hazards by 2027.

After starting in Asia, Flood Hub continues to expand globally. At the Sustainable with Google event in Brussels in October, Google announced the expansion of Flood Hub’s riverine flood forecasts to the US and Canada, covering more than 800 riverside locations where more than 12 million people live.

At the same time, technologists behind the project know there is more to be done, both in types of floods the forecasting addresses and in global reach. The intent is to eventually expand the service beyond riverine flooding, or rivers overflowing their banks, to include other flood types such as coastal and groundwater, while also extending the coverage to more parts of the world.

For people living in areas threatened by flooding, these advance notices are vital.

First and foremost, early warnings could save lives through evacuations, while also helping governments and residents protect property from damage—a transformative improvement, given the scale of economic setbacks that flooding exacts each year.

Reinsurance agency Swiss Re estimates that flooding cost the world more than $82 billion in 2021. With more warning, aid organizations are also able to provide assistance sooner, before disaster strikes.

For the teams behind these life- and property-saving advances, the project’s efficacy is proof of the power of AI to meet the world’s most pressing challenges—even those as intractable as natural disasters.

For Yossi Matias, VP of Engineering and Research and Crisis Response Lead, his commitment to leverage Google ingenuity against the elements was forged not in water, but in fire.

In 2010, wildfires spread through Mount Carmel in Israel, where Matias is based. He could see the flames from an office window, but online searches turned up no helpful details. His team mobilized, and within a few hours they made relevant emergency resources available through Google Search.

Relying on what the eye alone can see to issue emergency alerts for natural disasters is often not a tenable solution; warnings will come too late. That’s why the Google Crisis Response team has begun utilizing AI to inform their alerts.

One area where traditional alerts fall short, Matias says, is in explaining the potential for disaster. While alerts can detail how much a river is projected to rise—for example, 30 centimeters—that information doesn’t easily translate to what it can mean on the ground for a resident, their home or their village.

Pushing beyond that basic information required an effort to display easily understandable visuals—for example, projected water levels relative to human height, or expected water rise compared to prior floods.

To achieve this level of precision, machine-learning models ingest satellite imagery overlaid with 3D renderings of rivers and their surrounding elevations, adding to the data provided by the global hydrologic flood model.

The development of this model is a major breakthrough in the use of AI to mitigate the impact of natural disasters and helped Google bring Flood Hub to more than 80 countries in a matter of months.

Google Senior Research Scientist Grey Nearing characterizes Google as a nontraditional player in the flood forecasting space, in comparison to universities and government agencies. “But one thing that Google has is the ability to reach people,” he says.

In 2021, Google sent 115 million flood alert notifications to 23 million people through Search and Maps—everyday tools with which the average smartphone user is already fluent.

The hyper-localization capabilities of Flood Hub and of the Google Crisis Response alert network have helped people around the world cope with natural disasters. During Hurricane Maria in 2017, more than 15 million Puerto Rico residents received timely Crisis Response alerts.

Matias knows that with Google’s reach comes responsibility. Disaster alerts must be accurate, or recipients will lose trust in them and decide to tune them out.

“Evacuation could be very expensive,” Matias says. “Taking care of property is very expensive. Most people can only take those steps if they really know that the risk is real. So the ability to forecast flooding with a high confidence level—that’s the part that is very important, and the part that is very difficult.”

Accessibility is also a challenge. While Google has the resources to devote developer power to AI’s humanitarian potential, Matias and his colleagues recognize that, in the developing world, smartphone ownership remains far from universal.

That’s why Google Crisis Response partners with local Red Cross chapters and other aid organizations to identify volunteers who can use their personal devices to amplify the reach of Flood Hub warnings.

Findings from the Inclusion Economics team at Yale University, another Google partner, show that communities with local volunteers are 50% more likely to receive alerts before waters reach their area.

While Matias and his team measure success in alert reach and volume, and in the accuracy of their neural networks, he says the true measure of their effectiveness is the people and communities they help protect.

“What really matters is the helpfulness,” says Matias. “How helpful can we be to people? We see AI as uniquely positioned to help create a world where nobody has to lose their life in the middle of the night because they were surprised by a disaster.”