From Water to Watts: How Japan Is Powering Hydro Innovation

Takeaways

Japan is advancing hydropower innovation to meet 2050 carbon neutrality goals, using its long-standing expertise and regional partnerships like AZEC to support Asia's clean energy shift.

Key projects include Japan’s osmotic power plant in Fukuoka, which uses salt and freshwater to generate clean energy year-round. As the second such plant in the world, it aims to scale to global, water-scarce regions.

Japan also leads with a unique “owner's engineering” model, as seen in NiX Japan’s hydropower plant in Indonesia. The company handled all phases, boosting efficiency and community impact, and showcasing Japan’s practical clean energy solutions.

Summary by Bloomberg AI

Though winter may be approaching in the northern hemisphere, we should not forget that our planet is warming up, alarmingly fast. After a record-breaking decade, 2024 was the world’s hottest year with the global mean temperature rising 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.[1]

Driven by renewed urgency, most countries remain committed to climate targets and transitioning to a net zero economy. Japan is at the fore. Its government has renewed its promise to cut emissions and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.[2] Its Green Growth Strategy of decarbonization investments of up to 150 trillion yen continues.[3] And the country is leading decarbonization efforts for energy-hungry Asia through the Asian Zero Emission Community (AZEC), a Japanese initiative on decarbonization launched in partnership with ASEAN member states and Australia.[4]

One area in which Japan hopes to contribute to the global energy transition is in hydropower, a field where it has considerable expertise.

As a land with ample rainfall and mountainous terrain, Japan has long harnessed water for energy through dams, large and small, across its archipelago. Its accumulated know-how in water infrastructure, together with financing from Japan’s Official Development Assistance (ODA), has been used since the 1960s to help construct and operate numerous dam and hydroelectric projects, as well as water and sewerage systems worldwide, particularly in Southeast Asia.[5] More recently, the country has backed small-hydro projects in Nepal and partnered with Indonesia to build the largest hydropower plant in the region.[6]

Building on this track record, Japanese companies are pioneering new technologies and business models to help the world turn water into renewable watts, the Japanese way.

Two recent projects highlight Japan’s hydro innovation.

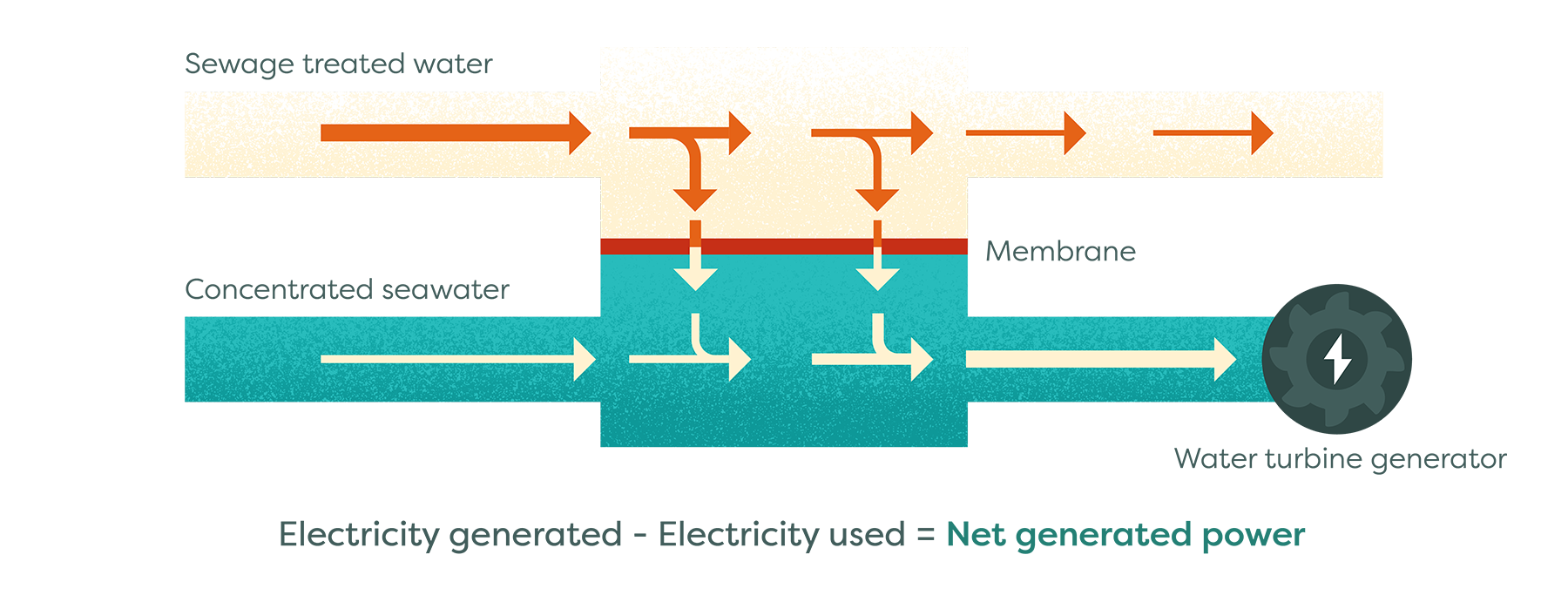

The first involves a new type of hydropower called osmotic power generation (or pressure-retarded osmosis), which has been highlighted by the World Economic Forum as one of ten top emerging technologies for 2025.[7]

The technology uses the osmotic movement of freshwater into saltwater through a permeable membrane to create a pressure differential force that can be used to turn an electric turbine. With the potential to generate clean baseload energy virtually all year round whenever there is a supply of fresh water and salt water (such as where rivers meet the ocean, or at desalination plants near sewage treatment plants), such osmotic systems can be crucial to our energy transition.[8]

In August 2025, the world’s second-ever osmotic power plant began operations in Japan’s largest desalination plant run by the Fukuoka District Waterworks Agency. (The world’s first is in Denmark, which started operations in 2023 and uses membrane technology from Japanese materials company Toyobo to harness energy from highly saline geothermal well water.[9] ) The newly inaugurated plant, designed and operated by Kyowakiden Industry, will use highly concentrated brine from the Fukuoka seawater desalination plant and treated water from a nearby sewage plant in Fukuoka City to generate up to 880,000 kWh of electricity per year, equivalent to the annual electricity consumption of 290 households.[10]

The plant opened after twenty years of research and development, says Dr. Tetsuro Ueyama, manager of the water treatment project at Kyowakiden.

“To improve efficiency to a viable level, we went through a lot of trial and error to keep the membranes operating stably and keep them clean for consistent output,”[11] notes Ueyama.

The next steps are to scale up osmotic power technology so it can be deployed in much larger desalination plants in water-scarce regions like the Middle East, says Ueyama. Kyowakiden has also been researching how to generate osmotic energy from sea water, which has a lower concentration of salt than desalination brine. This will make the technology viable for cities in coastal areas that do not have desalination plants.

“Our initial goal was to reduce the amount of electricity consumed by our desalination plant by tapping unused resources,” says Kenji Hirokawa, manager at the Fukuoka District Waterworks Agency Sea Water Desalination Plant. “Now we hope that the technology developed here spread further to contribute to global-scale climate solutions.”

Another hydropower contribution from Japan is an unusual “owner's engineering” approach for overseas hydropower plant projects, in which one company designs, constructs and operates hydropower plants as majority ownership position.

In 2023, NiX JAPAN, a company based in Toyama with a background in public infrastructure engineering for bridges, roads and parks, successfully began commercial operations of the Tongar Hydro Power Plant in West Sumatra, Indonesia, with a generation capacity of 6,200kWh and an annual power generation of 38,730MWh, or the equivalent of 46,000 Indonesian households’ annual electricity consumption. NiX JAPAN has a 25-year contract to sell electricity to the Indonesia’s state-owned power company PT PLN.

Unlike most of the hydropower projects that Japanese companies and governments have been involved in, this project is unique in not being funded by ODA. In large part, it was financed through low-interest loans from Japanese banks during the high-risk construction phase, and later refinanced by PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur (Persero), Indonesia’s state-owned infrastructure financing company. The project received partial subsidies for its turbine equipment through the Joint Credit Mechanism (JCM) scheme, which was set up by Japan in 2013 to partner developing countries in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[11]

The success of the Tongar Hydro Power Plant is due to perseverance and localization, explains Wataru Yoshio, director and executive officer of NiX JAPAN.

Originally a banker with expatriate experience in Indonesia, Yoshio spent ten years leading the Indonesia’s project. In addition to securing funding in Japan, he lived in Indonesia for more than half a year, negotiating with local stakeholders, inspecting potential hydropower plant sites, establishing local subsidiaries and managing the project. Yoshio also hired Indonesian engineers, contributing significantly to the local economy and sharing Japanese construction know-how. As a part of its contribution to the local community, the company also promoted various community activities, including the maintenance of local village roads.

The success of owner's engineering also depends on economic viability and joined-up planning. For example, NiX JAPAN streamlined Japanese engineering standards to local conditions to ensure the viability of the power plant. During planning and construction, NiX JAPAN used advanced engineering software to create 3D and 4D simulations (with 4D adding a time axis to visualize construction sequences), which ultimately improved construction quality and project management efficiency. The Tongar hydropower plant is generating more electricity than planned – an unusual situation for overseas hydropower projects, explains Yoshio.

“Rather than different players doing separate parts of the project, we designed and developed an integrated scheme and long-term mindset as an owner. This translates into greater returns over time,” says Yoshio.

With a rapidly growing population and economy, suitable terrain and climate conditions, Indonesia and other parts of Southeast Asia will be important markets for companies like NiX JAPAN, which are bringing hydropower to the region.

And with more unused desalination brine from new desalination plants coming online in many parts of the world as well as a growing number of heavily populated coastal cities, there is much untapped potential for the kind of osmotic power solutions being pioneered in Fukuoka.

Both new hydropower projects are examples of Japan’s technological ingenuity, perseverance and determination. If these solutions can be scaled and replicated more broadly, we may be in a watershed moment for the energy transition.

Sources

[1] World Meteorological Organization [2] Reuters [3] Reuters [4] Kizuna [5] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan [6] The Investor [7] World Economic Forum [8] World Economic Forum [9] SaltPower [10] Fukuoka District Waterworks Agency [11] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan [12] World Economic Forum