The Cities Showing How Skills & Innovation Could Build the UK's Future

Innovative businesses and a skilled population create a virtuous circle, each fuelling the growth of the other—and investment is what underpins both. What can businesses learn from the UK urban centres already on the way to reviving their cities and surrounding regions?

Hull: The UK’s “Energy Estuary”

Kingston upon Hull and the surrounding region of the Humber has been a centre of maritime industry for centuries, but the decline of shipbuilding and the fishing industry left the city as one of the UK’s poorest. Despite its economic difficulties, Hull remains a key centre for the manufacturing industry, and today, the Humber is being reimagined as a hub for renewables, boosting opportunities across the region.

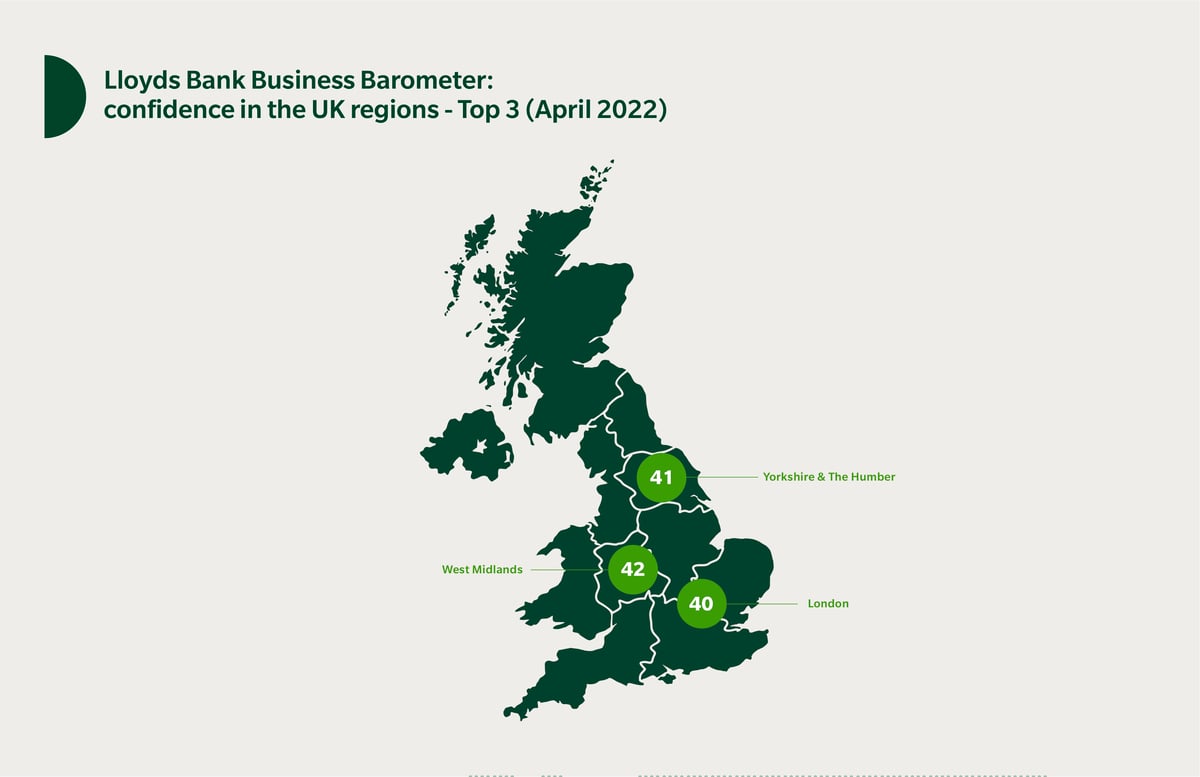

The Lloyds Bank Business Barometer surveys businesses across the UK to gain an insight into business confidence, employment trends and business activity—and its April 2022 report found confidence to be 42% in Yorkshire and the Humber, ranking it second of the 12 UK regions in terms of business confidence, and just ahead of London.

Early investment in Hull’s renewables sector came from the world’s largest manufacturer of offshore wind turbine blades, Siemens Gamesa, which invested heavily in training a local workforce and has created 1,200 jobs in the region since opening its offshore blade factory in 2016. The company is currently investing a further £186 million to expand its turbine blade manufacturing site.

The cluster effect on innovation and skills has attracted other leading players in the sector, including GRI Renewable Industries, which has announced plans for a £78 million turbine manufacturing plant in the region. Meanwhile, the UK government has recognised Hull’s vital role in the energy transition and is investing £160 million in the region’s renewable energy industry.

“The Humber offers one of the best examples of successful UK clusters,” says Chris Sood-Nicholls, Managing Director of Regional Development at Lloyds Bank. “Siemens has been very clear on what it is doing, and when a business makes a commitment, other people can plan on the back of it. Small businesses can adapt their production to meet demands, while the university and other higher-education institutions can look at what they can do from a skills perspective.”

The region also illustrates the potential of the private sector and educational institutions to work in parallel to build expertise and skills that can revive cities and regions. The University of Hull, with its Energy and Environment Institute and Centre for Sustainable Energy Technologies, has become a centre of renewable energy research.

“Our Energy and Environment Institute is the pivot of a lot of this work. Four years ago, there were fewer than five people at the institute, and today there are 170,” says Professor Susan Lea, Vice-Chancellor at the University of Hull.

She adds that Hull’s reputation as a centre of excellence for renewable energy is an attraction for students. “The younger generation are very aware of the challenges that society is facing, so they are concerned to see a university not just talking about this stuff but acting upon it. It’s also attractive at the postgraduate level. We have the Aura Innovation Centre [AIC], which is centred around innovation in renewable energy, and, within that, we have a doctoral training centre.”

The AIC is a model example of private- and public-sector partnerships working to drive economic renewal and innovation. Led by the University of Hull, the AIC is supported by a wide range of organisations, including the Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult and Siemens Gamesa, which in 2019 partnered with the AIC to offer the UK’s first offshore wind degree apprenticeships.

“Where clusters have worked well, there has always been a long-term bridge between the private sector and academia, which creates perfect conditions for high-value sectors, a skilled workforce and high business investment,” explains Ahmed Goga, the CBI’s Director of Regional Policy.

Andrew Connors, Lloyds Bank’s Head of Public Sector and Higher Education, says Hull is a prime example of how universities are playing a bigger role in economic innovation and renewal.

“Universities are a world-class sector for the UK. They have shown great agility through the pandemic and continued to be really successful in driving demand for international students. But some universities, like Hull, are also looking to drive a realignment of their missions and strategy to address regional social and economic demands,” he says.

Hull has some way to go before it can be said to have regained its former glory as one of the UK’s most prosperous port cities, but as it carves out a new identity in the 21st century, it is already a prime example of the potential of renewal through innovative technology and new skills.

Bristol and the Silicon Gorge

Business confidence in the South West has risen by 16 points since March this year, according to the April 2022 Lloyds Bank Business Barometer, while Bloomberg UK’s Levelling Up Scorecard demonstrates that productivity is on the rise in Bristol and its surrounds, with the productivity gap closing by 2.1% between 2019 and Q4 of 2021 alone. Inextricably linked to skills, jobs and the health of local economies, productivity is considered one of the key factors in the country’s ability to level up.

Benefitting from excellent local universities, years of investment in infrastructure and its proximity to London, Bristol has emerged as a key centre of innovation in digital technology, with some observers dubbing the city and its surrounding region the “Silicon Gorge.” The tech sector in the South West has a turnover estimated at £9 billion, with digital and tech firms there employing more than 68,000 people, and more than half of these jobs are in Bristol, where the sector is rapidly expanding. According to the government’s Digital Economy Council, there was a 50% rise in the number of tech job opportunities in Bristol between 2020 and 2021.

Thanks to its growing workforce of skilled digital professionals and the healthy talent pipeline provided by local higher-education establishments, the city is attracting significant investment. Last year, Bristol’s tech firms attracted £100 million of venture capital funding, according to the Digital Economy Council, with investors attracted by cross-sectoral opportunities in tech and engineering.

As businesses flock to Bristol, so do their workers; the city’s population has grown by a staggering 10% in the past decade, with an average age of 32, compared to the national average of 40 in England and Wales and 36 in London. Bristol’s dynamic, innovative population helps the region contribute £40 billion to the UK economy, while its thriving business ecosystem creates the ideal environment for companies small and large to maximise growth.

Partly due to its excellent transport connections, several major companies in the tech and telecom sectors—including EE, BT and Vodafone—have a substantial presence in Bristol. This has fed its emergence as a tech hub, as such larger organisations stimulate the growth of support and supply businesses.

“There’s always going to be an anchor of large employers in a city or town, but SMEs also play a vital role, not only as part of the supply chain for those larger businesses, but as innovators in their own right,” points out Chris Sood-Nicholls of Lloyds Bank. “Many of our greatest innovations come from small companies and startups, so it’s important that they have the environment to thrive, with access to finance and to the right spaces where they can collaborate and co-create.”

One reason Bristol has emerged as a leading UK technology hub is the strength of its universities. The University of Bristol launched the Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in 2016, while the University of the West of England is home to its own Enterprise Zone that includes a community hub for startups.

The University of Bristol is also home to the Bristol Quantum Information Institute, one of two UK Research and Innovation-funded Centres for Doctoral Training in quantum engineering. It boasts more than 60 active Ph.D. candidates and extensive links to industry. Local government investment of £35 million enabled a pilot of the Quantum Technologies Innovation Centre to open at the university last year, and by 2025, it is expected to operate as the world’s first open-access innovation centre for quantum technologies. The centre is projected to generate £232 million of added value to the local economy in its first decade and will create an estimated 360 jobs.

In addition, Bristol’s Quantum Technology Enterprise Centre is a pre-incubation programme that has created more than 30 new companies and helped them raise £60 million in funding. The centre is responsible for one-third of active UK quantum engineering startups.

Proactive steps by business finance providers and the public sector are vital to drive regional economies to the next level. In the case of Bristol, a range of stakeholders has come together on several initiatives to boost tech entrepreneurialism in the city. One such effort is Engine Shed, a collaboration between the University of Bristol, the Bristol City Council and the West of England Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) that is a hub for startups, academics, small businesses and larger corporations, and aims to create a network of innovation for the city.

It’s vital that these success stories remain local. SMEs and entrepreneurial businesses that may grow into giants need to feel that they can keep growing without having to move elsewhere. “They need an incentive not to leave, and that means an environment of innovation and skills that comes from larger businesses in the same sector,” Sood-Nicholls explains. “These small companies can then be a city’s greatest successes, and that is a huge contributor to a city’s future longevity.”

Bristol is home to numerous companies that have grown from small beginnings to become major businesses, among them three tech unicorns (private companies with a value estimated at $1 billion—roughly equivalent to £800 million—or more). The government predicts this figure will double to six in the next few years.

These businesses together form the region’s impressive tech ecosystem, which has not only earned it the Silicon Gorge moniker but will help ensure that Bristol thrives as a destination for innovation, employment and investment for decades to come.

Keys to a thriving future

Hull and Bristol are just two examples of the UK’s thriving cities, and they illustrate key themes and lessons that can guide other regions and their businesses.

Capitalising on a city’s heritage can be a real advantage. Existing industries and businesses have links and synergies with other sectors and can be part of an evolution and adaptation. For example, Hull’s maritime engineering support skills and supply companies can now support offshore wind technologies, while Bristol’s aerospace engineering legacy has fostered a new generation of students and startups pushing the boundaries of semiconductor technology and quantum computing.

Partnerships between academia and business can create centres of excellence in emerging technology that are mutually beneficial, stimulating innovation and skills in educational institutions and creating employment and opportunities for those skills. Meanwhile, partnerships between large businesses and SMEs are also mutually supportive, creating local supply chains and a wider and more varied market for skilled employees.

Investment is key—and the opportunities for business to play a role are many. Companies seeking to invest should ensure that their financing is attuned to a region’s potential, taking into account its established and emerging innovation hubs. Working closely with the public sector and other private-sector partners is also crucial in driving entrepreneurship and boosting the future of the UK’s most promising cities.