Reducing Variations in Care Will Save Lives and Cut Waste

Standardizing medical best practices will underpin the future of value-based healthcare.

Hospital admissions in Australia and Germany are double the rate of those in Canada and Spain, according to OECD figures. Knee replacement rates are four times higher in Switzerland, Finland and Canada than in Israel and Portugal. And the residents of Manchester, England are more likely to die of heart disease than residents of nearby Birmingham, even though their populations share similar characteristics, according to the U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS).

These stark and sometimes disturbing differences in healthcare and survival rates are prevalent around the world. Shocking disparities occur between countries, regions and cities, between hospitals and even between doctors. Wide variations in medical care and medical results are a block to creating high quality healthcare and optimal outcomes.

Reducing unwarranted clinical variations is essential to creating value-based health systems which drive standards up and costs down. Some variations reflect differences in the wealth, health, age and environmental conditions of patients. But many are down to unacceptable divergences in the way physicians administer treatments, prescribe drugs and follow clinical procedures.

And it’s not just doctors. The methods nurses use to treat bed sores are “never the same twice” according to Dr. Brent James, former Chief Quality Officer at Intermountain Healthcare. Speaking at the recent Siemens Healthineers Executive Summit , he added that the “grand champions” of variations are physical therapists. Encouraging doctors, nurses, therapists and hospitals to use the best, most cost-effective treatments every time will boost value and save lives. Of course, every patient is different. But the care they receive should vary according to their individual needs, not because health systems happen to have different ways of doing things.

The problem has become systemic. As Dr. Jonathan Darer, Chief Medical Officer at Siemens Healthineers told the summit: “We have created a practice environment designed for maximum distraction. People cannot keep up. When a patient comes in we know what to do - we stabilize them, we create a period of calm. Our healthcare system is beginning to look like an unstable patient. We believe that by removing unwarranted variation we can bring order and a much-needed sense of calm to the practice environment.”

Uncovering and ironing out clinical variations requires careful examination of data. Dr Ari Robicsek, Chief Medical Technology Officer at Providence Healthcare, based in Washington State, told the summit that all medical professionals should have an opportunity to learn from each other. To achieve this, he has created a statistical tool that allows doctors and hospitals to carry out detailed comparisons of outcomes and costs for different operations.

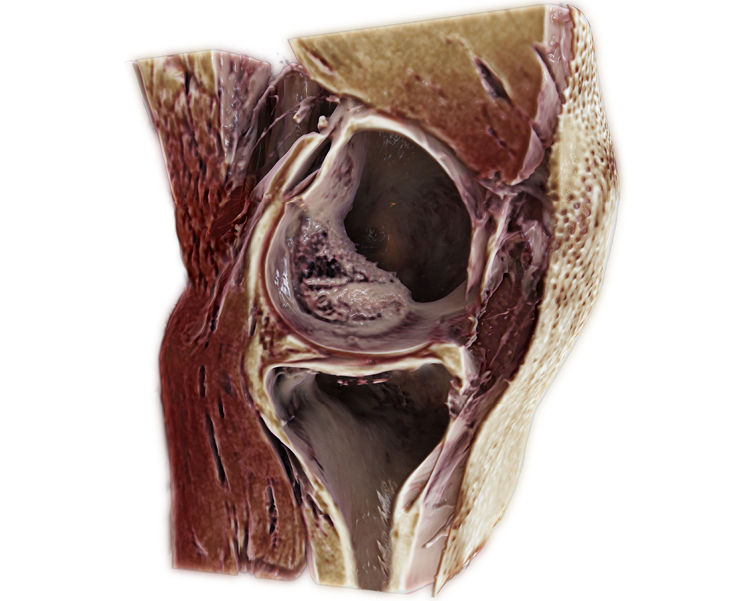

Robicsek pointed to knee replacements, where the costs of operations in U.S. hospitals can vary between $6,600 and $10,000. One factor behind this difference is that some surgeons use cement impregnated with antibiotics in their operations, which is three or four times more expensive than non-antibiotic impregnated cement. Robicsek analyzed some 20,000 knee replacement operations over two years, keeping a close eye on bone cement costs and infections related to the operations. He calculated that in many cases, there was a low risk of infection, so the use of antibiotic cement could be reduced. “We were able to achieve a $75 reduction in bone cement costs per case, which matters when you do 10,000 cases a year,” he said.

Clinical variation is often down to overuse and underuse of drugs and medical procedures. Professor Matthew Cripps, Director of Sustainable Healthcare for NHS England, said that most overuse occurs in the acute care sector. But underuse tends to be widespread in secondary prevention - detecting a disease early and stopping it from spreading.

“Fixing this means shifting market share towards the parts of the system that do secondary prevention,” Cripps advised. This gets to the heart of improving the value in health services; reducing unwarranted variations means health providers can achieve better care so costs can be reduced. He said that Manchester’s higher death rate from heart disease compared with the aforementioned Birmingham is all the more surprising given that Manchester spends more on the problem.

Cripps said that doctors and health professionals might seem resistant to change, but that they are willing to reduce variations if achievement of improved outcomes is clear. “Clinicians are evidence-based creatures, so use evidence to show where their behavior is the cause of unwarranted variation,” he said.

In the search to achieve greater standardization of care, healthcare experts are looking to the manufacturing and retail industries, which have long excelled in creating quality and production standards.

Dr Mike Modic, Senior Vice President, Population Health at Vanderbilt University, in Tennesse, has studied industrial manufacturing processes to find lessons for healthcare. He said it was “gobsmacking” to realize that manufacturers had developed processes to reduce variations that had not occurred to healthcare managers. Industrial manufacturers achieve standard output by analyzing huge amounts of data about the costs and outcomes of procedures and adapting processes to iron out any kinks.

“In most cases we know what the right thing is to do,” said Modic at the summit. The question is how do we enable it in the workflow, how do we get everybody to do that? It really is in our grasp,” he said, adding that relevant data on costs, outcomes and patient satisfaction should be embedded in electronic medical records.

Modic has been involved in tests where variations were reduced and costs were kept down while maintaining similar or better outcomes; however, greater efficiency cut revenues. “To be honest, we decreased revenue because we decreased utilization,” he acknowledged. For insights on managing population health, Modic turned to the retail industry, which gathers all sorts of lifestyle and behavioral data about shoppers.

“We know the medical data, but we should also know the cognitive and behavioral aspects of the patient, the social side such as whether they have a partner or whether they drive. All of this should live in the EMR but it is in discreet locations - it is never brought together and synthesized so you can look at the patient holistically where social determinants are factored in,” he said. Retailers collect this broader data about their customers and hospitals need to do the same for patients, he argued.

Meanwhile, Dr. James, pointed out that modern medicine has become highly complex and this makes it hard to identify the reasons for variations and then manage them. “Most of the advances we’ve seen in reducing variations come from managing the context,” he said. But it is up to senior managers to create the conditions where variation can be reduced: “The primary group that creates that environment is the leadership team.”

James explained that the main tool that has emerged to reduce clinical variations is the “shared baseline protocol”, which involves embedding best-practice guidelines into clinical processes. These guidelines can be shared with other doctors who may vary them according to the needs of the patient. The aim over time is to eliminate variations among professionals but to retain variations related to patients.

Healthcare costs are rising faster than the growth rates of the world’s economies as populations live longer, chronic conditions multiply and expensive new treatments come on stream. Keeping waste to a minimum and improving value is vital. Many studies show that at least 30 percent of U.S. health spending is considered wasteful according to many studies and much of that waste could be eradicated if unwarranted variations in care were reduced.

Healthcare providers are pouring resources and research into reducing unwarranted clinical variations. Reducing these differences is essential in creating a value-based healthcare system fit for the 21st century.

Written by David Benady, for Bloomberg Media Studios

Related links

How to reduce unwarranted variations in healthcare? Learn more from Brent James

What will the future of healthcare look like? Learn from experts

Expanding precision medicine. Explore how

Footnotes

1)FOCUS on HEALTH Geographic Variations in Health Care © OECD, September 2014