Taking Cities to the Next Level

With city infrastructures largely built already, much of the work to create the urban hubs of the future will involve reconfiguring the existing built environment. Is our tech up to the task?

A generation ago, New Rochelle, N.Y. was a zombie city. With a declining and hollowed-out urban core, the New York City suburb was “almost left for dead,” according to its mayor, Noam Bramson.

Many residents felt that there was nothing worth staying for, triggering a big population exodus. But today, New Rochelle is undergoing a bold transformation that has made it one of the fastest-growing areas in New York State.

A new zoning code introduced in 2015 has allowed the city to encourage sustainable, people-centered development, and to reverse poor planning decisions of the past. For example, a six-lane highway that sliced a historically black neighborhood in two is being turned into a local street and linear park, reconnecting the city center, train station and library.

Urban planning strategist Rebecca Karp hails the city for centering its efforts around the idea of a 15-minute city, where people are able to live, work, shop and spend their leisure time within a short walk or cycle ride.

“New Rochelle rezoned its entire downtown district to build much-needed new housing, of which there’s a severe shortage across the region, and the city’s planners are about to redesign its existing transit center – a facility that is at the heart of the city’s transit system,” says Karp.

Her company, Karp Strategies, has helped ensure that the city’s transformation is truly people-led, and it even designed a virtual reality (VR) kiosk offering simulations to bring the new plans to life. “Folks could put on VR glasses and see projections of the development, and they could give feedback that would directly influence the designs and planning,” she says.

New Rochelle rezoned its entire downtown district to build much-needed new housing, of which there’s a severe shortage across the region

— Rebecca Karp, Urban Planning Strategist

Housing imbalance

The concept of the 15-minute city was first popularized by Carlos Moreno, a business professor at Sorbonne University, in Paris. It was embraced by the C40 group of nearly 100 mayors worldwide as a way for cities to regain resilience after the Covid-19 pandemic.

The potential benefits of this model are wide-ranging. Besides delivering cleaner air by reducing unnecessary travel, the proximity to amenities in a 15-minute city creates a stronger sense of community, and better health and well-being are expected to be natural consequences.

Yet the key principles are not new, and they have underpinned major planning initiatives for decades, according to developer Jonathan Rose, founder of US affordable housing pioneer Jonathan Rose Companies. He points to former mayor Mike Bloomberg’s pedestrianization efforts and expansion of bicycle lanes in New York City in the 2000s, and London’s long-running reclamation of the Thames waterfront.

What New York City and London lack, says Rose, are affordable accommodations to match the needs of workers, families and older people. “Both cities are way off on that balance, and, as a result, they don’t have enough affordable housing,” he says. When households are exiled to affordable areas, far from workplaces, “it creates all kinds of economic, social and transportation issues.”

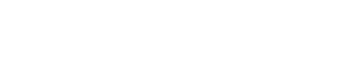

The housing shortage is fast becoming a global issue, set to affect 1.6 billion people by 2025. A global study of 200 cities, comparing house prices with average incomes, found that 90% were unaffordable to live in. The US alone is short 1.5 million homes.

For many people, says Rose, the enforced domesticity of pandemic lockdowns exposed the unsustainability of the long daily commute that had disconnected them from their families and their local communities. He believes that the successful cities of the future will need to be mixed-income, mixed-use and intergenerational.

Buildings reimagined

The continued embrace of hybrid working since the pandemic has left many city centers diminished, and “zombie buildings”—with occupancy at or under 50%—have become a widespread phenomenon. Demand for office space has fallen further in 2023 in London and many US cities, leaving vacancies at a 20-year high.

Karp believes mixed-use buildings need to be factored into the cities of the future, and Schindler, known for its elevators, escalators and moving walkways, is helping to facilitate this shift. Frankfurt’s 190-meter Omniturm building, for example, blends office, residential and public spaces. It uses technology to route visitors or residents to where they need to go. They identify themselves at the entrance using a smartphone, chipcard or temporary access code, and Schindler’s transit management technology assesses their access rights and designates the nearest elevator.

This level of connectivity also means the spaces can run more efficiently. By connecting units in the cloud, Schindler can detect anomalies at an early stage, troubleshooting remotely in some cases. Early-stage detection means technicians already know what the issue is before arriving onsite. Equipped with the right tools, unnecessary field trips are eliminated, which in turn can embed carbon efficiency into the system.

With 80% of the buildings of 2050 already in existence, we must adapt what is there, and design those adaptations for a high degree of flexibility

— Florian Troesch, Schindler

Flexible elevator systems

Schindler is now turning its attention to the need to retrofit buildings for multiple uses. “It is clear that, with 80% of the buildings of 2050 already in existence, we will not be able to start from scratch. Rather, we must adapt what is there, and design those adaptations for a high degree of flexibility,” says Florian Troesch, Schindler’s Head of Transit Management and Digital Ecosystem.

Schindler’s new MetaCore solution—an elevator retrofitting system that enables the flexible evolution of buildings—means that elevator systems can be reconfigured at will, as often as needed.

“This is in stark contrast to elevator systems of today, which are typically designed around the original building use and can require very expensive construction coupled with equipment upgrades to accommodate mixed-use retrofits,” says Troesch.

By helping to save buildings from potential demolition because their original use is outdated, Schindler MetaCore could also help to reduce carbon emissions.

The technology means that building owners can use their spaces to their maximum potential, with multiple uses per floor, including residential, office, commercial and institutional. Schindler provides support with virtual simulations to test different configurations before any physical work begins.

Troesch hopes the results of this technology will provide support to the concept of the 15-minute city—which some conspiracy theories suggest is more about controlling people’s mobility. “Far from being a constraint on travel, we see this type of urban topology as one that allows its inhabitants to have choices,” Troesch says.

For Rose, it’s about presenting the concept of 15-minute cities as a return to tradition. “The classic English villages, with high streets, houses and schools, are 15-minute neighborhoods,” he points out. “In a sense, we’re trying to create more of the best communities that we already have.”

The classic English villages, with high streets, houses and schools, are 15-minute neighborhoods

— Jonathan Rose

-

Preserves history

Allows historic buildings and cultural landmarks to be retained -

Reduces waste

Construction debris makes up an estimated 63% of the UK's annual waste -

Cuts emissions

It takes between 10 and 80 years to offset the negative climate effects of a new building construction

The Benefits of Repurposing Buildings