Alternative Investments Are Gaining Ground, but Can They Still Deliver?

After a decade on the rise, alternative investments are no longer a peripheral category of capital markets, but a core part of the craft of modern asset management.

From pension funds and insurers to private banks and family offices, allocations to private equity and credit, real estate, infrastructure and hedge funds have expanded, along with the role they play in managing risk, return and liquidity.

But as the alternatives market matures and macro conditions continue to tighten, a growing number of allocators are rethinking how and why they use alternatives—and how to preserve the very value that made the asset class attractive in the first place.

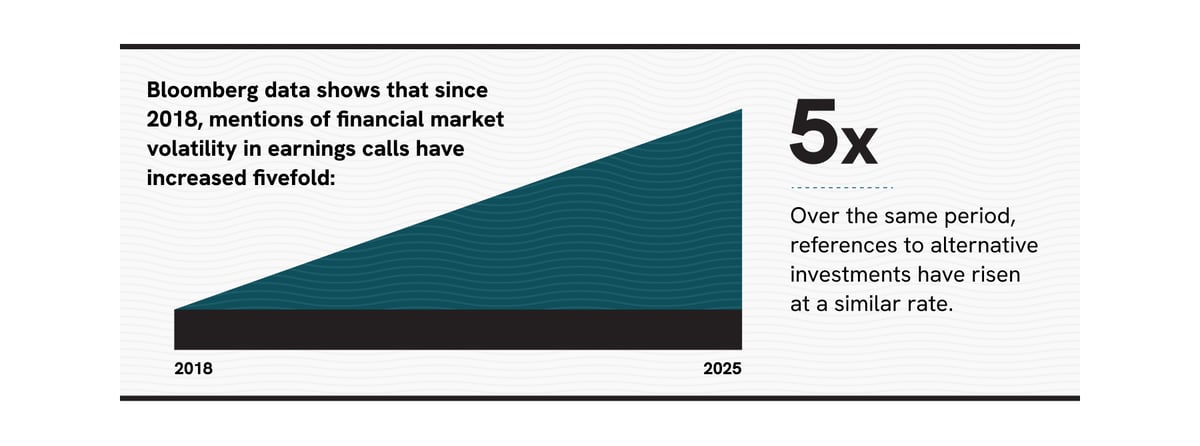

Bloomberg data shows that since 2018, mentions of financial market volatility in earnings calls have increased fivefold, and over the same period, references to alternative investments have risen at a similar rate. “When you look at alternatives, you’re not just protected, but arguably more protected in a risk-adjusted way,” says Johannes Roth, Co-Head Unified Global Alternatives at UBS Asset Management.

That risk-adjusted appeal has helped close the gap between institutional and private wealth portfolios, and private clients now approach portfolio design with objectives similar to those of mega-funds.

“Aside from tax considerations, there’s no reason why a sophisticated private investor should allocate capital any differently than an institutional investor,” says Jerry Pascucci, also Co-Head Unified Global Alternatives at UBS Asset Management.

But this convergence has been driven by necessity, as higher-for-longer interest rates, persistent inflation and regulatory pressures have forced a fundamental rethink of the traditional 60/40 equity-bond portfolio.

Concerns about volatility became even more pronounced in early 2025, and allocators began to shift their attention from traditional strategies toward private credit, hedge funds and digital platforms, amid SEC scrutiny of fund structures.

For the first time, the question is no longer whether to allocate to alternatives, but how.

Semi-liquid evergreen funds, curated fund-of-funds investment vehicles, secondaries and multi-manager platforms are now table stakes for anyone seeking scalable, diversified exposure and portfolios that behave with resilience when markets seize up.

“Wealth clients’ portfolios would look totally different from the ones that institutional investors have, and we’re trying to bridge the gap in order for them to have access to thoughtfully constructed portfolios,” says Roth. “This is a pretty unlevel playing field.”

As demand rises, the opportunity is clear. McKinsey & Company estimates that private wealth alone could bring $500 billion to $1.3 trillion into alternatives by the end of this year.

Private credit, one of the most closely watched parts of the market, has thrived in a low-rate environment; as banks retreated, direct lenders stepped in. But with rates expected to stay higher for longer, borrowers are under pressure, and regulators are taking a closer look at how valuations and structures are being managed, putting this asset sub-class under scrutiny.

But Roth remains confident. “The real question is whether you’ll continue to see durable premiums above liquid fixed income,” he says. “The universe for us is not the uber-risky part of the market. It’s direct lending and other opportunities with floating rate characteristics, sponsor-backed companies and triple-digit EBITDA.”

Pascucci agrees, but notes that investors need to look beyond labels to make smart decisions. “Investors shouldn’t be confused by the semantics and the noise,” he says. “What they should be focused on is the merits, the quality, the underwriting."

“The term I always use is: content over container. Do you understand your content, and does that content belong in the container it’s in?”

Private equity, too, is adapting to new market conditions. Weaker IPO and M&A activity has extended holding periods and forced managers to find new liquidity options. GP-led continuation funds, NAV-based loans and the rise of secondaries have become key to portfolio management.

“I’ve seen secondaries move from being something used really at the margin, when people were desperate for cash, to a core strategy,” says Diana Celotto, Co-Head of Unified Global Alternatives – Private Equity at UBS Asset Management.

Still, Celotto sees opportunity, particularly in the long-term nature of private equity investments.

“The private equity world has paused a little bit because of what’s happening with tariffs; it could lead to a lot of change,” she says. “It’s not surprising right now that GPs, or any investor, are taking a long-term view of companies.”

With the first wave of adoption complete, the alternatives market is entering a more selective phase, forcing investors to think more strategically. “The first-mover advantage is clearly over,” says Pascucci. “It doesn’t mean the total dollars into those things will flatten; it just means that the trajectory will flatten.”

To address this, product innovation is likely to continue, but investors will become more discerning. “Just because there’s not a shortage of product doesn’t mean there isn’t a shortage of best-in-class product,” says Pascucci.

Ultimately, alternatives will remain a core part of the portfolio mix not because they are novel, but because they behave differently when markets dislocate.

“What I love about the private markets is that they are courageous in the most important times,” Pascucci says. “Owing to the illiquid nature of private markets offerings, investors are able to engage in dislocation opportunities with less latency than listed securities investors tend to do. The profile of this capital therefore enables the potential for broader up-capture of these opportunities on an absolute and risk-adjusted basis.”