Why the Odds Remain Stacked Against Female Economists

Since the Nobel Prize in Economics was introduced in 1969, it has been awarded to 75 men, and Elinor Ostrom.

This startling gender disparity at one of the world’s most prestigious awards to celebrate outstanding achievement, represents just the tip of the iceberg for economists.

The average age of Nobel laureates in economics is 67, and at that level of experience and seniority, there remain few female economists today. Why does this gender gap exist?

To try and get to the source of the problem, attention is now being focused on what is happening in the preceding, formative years of economists.

Examining the pipeline

For many practitioners and researchers in the field, part of the problem seems to be within the education process itself. From the outset, women are under-represented in economics.

According to figures from the American Association of University Women (AAUW), there are three male economics majors for every female. In the report, “Why So Few?”, published in 2010, the association cited eight studies that provide evidence that social and environmental factors significantly contribute to the under-representation of women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM).

It seems obvious: When teachers and parents positively support the view that young women can hone and develop their academic performances with experience and learning, they do better on tests and are more likely to continue in their studies.

This is true for all students, but is found to be notably relevant for girls and young women in mathematics-related subjects, where negative stereotypes persist about their abilities.

The AAUW report concluded that by creating a “growth mindset” environment, teachers and parents can actively help change the gender ratio.

Nobel laureate Ostrom herself spoke publicly about her struggles against the impediments of the system.

During her college years, Ostrom faced hurdles common to many women of her generation, saying she had been actively discouraged from pursuing any Ph.D., not least one in economics.

She graduated from UCLA with a Ph.D. in political science, where she was one of only three women in a class of 40 students.

In her autobiography written at the time of her Nobel award, Ostrom recalls: “We were told after we began our program that the faculty had a very heated meeting in which they criticized the departmental committee for admitting any women and offering them assistantships. Fortunately, our fellow male graduate students were friendly and encouraged us all to continue in our program.”

For Paul Donovan, global economist and Managing Director at UBS Investment Bank, reaching women early in their education is vital to the long-term goal of achieving more female leaders in the field.

“Attracting women to the economics profession at an early stage is important,” he says. “One of the things I try to do in my role is to visit and talk to schools, and explain the important role economists can play in society.

“Anecdotally, I have been getting more requests from all-girls schools in recent years. I still get lots of requests from all-boys schools as well, but there does seem to be a shift in terms of interest, and more deliberate attempts, perhaps, on the education side to try and broaden things out.”

Progress has been made since Ostrom’s own school days in the 1950s, with the number of women represented in economics at Ph.D. level in the U.S., and many parts of Europe, rising from fewer than 10 percent to more 30 percent in many institutions during the last half-century.

Explaining the “women who simply disappear”

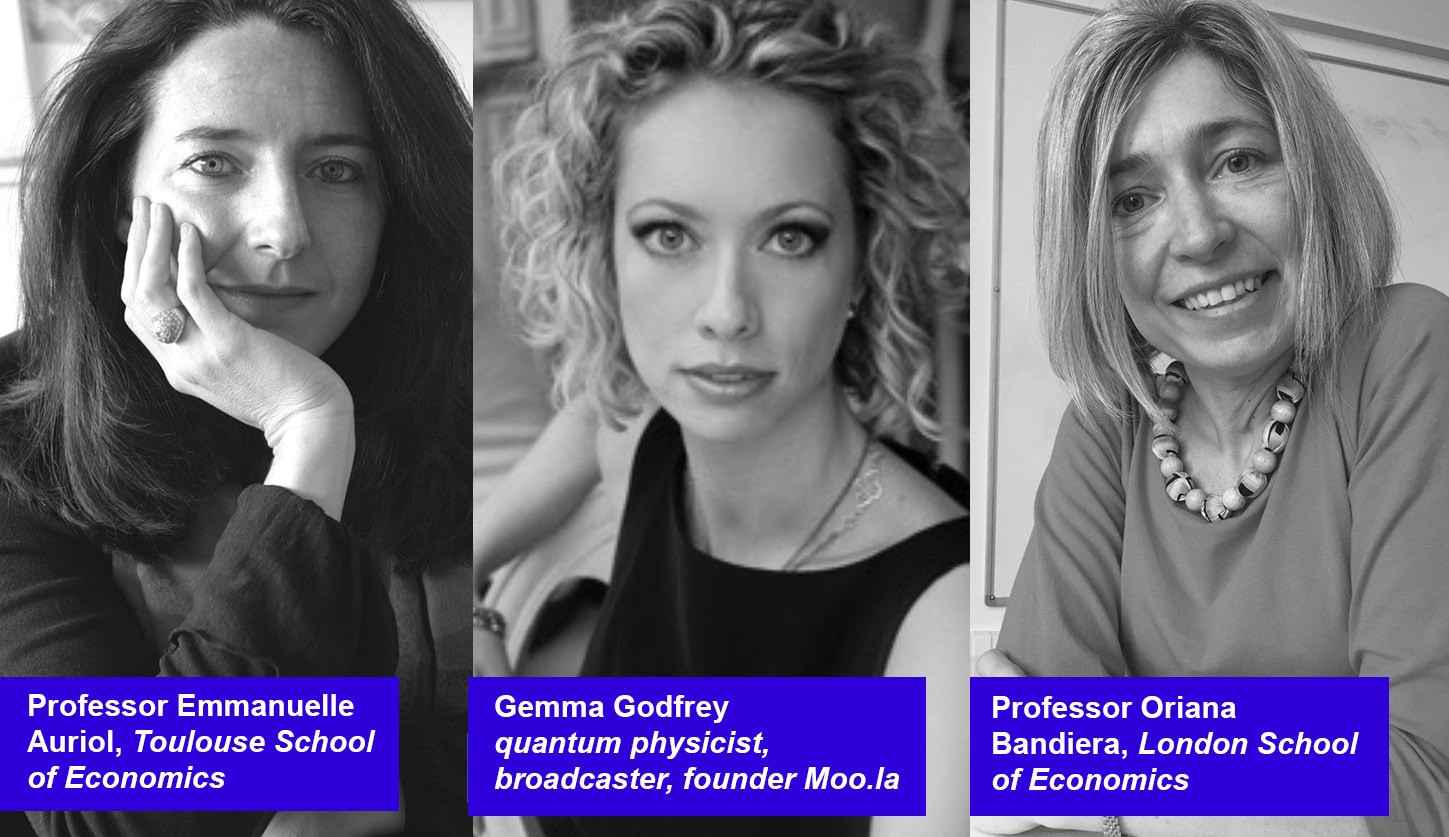

One major source of concern today are the huge swathes of potentially brilliant female economists who leave the sector after attaining a Ph.D., says Professor Oriana Bandiera at the London School of Economics.

“I’m 43 years old, and the show of women in economics even at my level is very low,” says Bandiera.

“There is a pipeline problem. If you look at [the gender mix of] students now, we’ve largely reached parity [at LSE], but already at assistant professor level you start to lose that parity.

“At associate level, you are talking about 30 percent women, and at full professor level, that shrinks to about 15 percent in most departments.”

Bandiera believes the mystery of the “women who simply disappear” from the sector can be attributed to the demands of academia.

Long hours are required for research, and, once coupled with teaching and administrative duties and the relatively low pay in the early years, can make for an unappealing career path.

“In a top department in the U.S. you’re looking at 80, 90, up to 100 hours per week,” she explains.

“In the U.K., it’s less extreme, but, if I think of my colleagues at the top departments — certainly my most senior and successful colleagues — if they are not in the office every single hour of the day then they are certainly contactable. If I email them on Sunday morning at 7 a.m., they will reply within half an hour.”

In an attempt to better explain the culture, where success is measured by the quality of papers produced, Bandiera says: “It is a choice. People really like the work. It really is quite engrossing when you get into it.

“I think it’s a combination that it is genuinely interesting for the people doing it, plus the fact it is relative; it’s like a tournament, only the best succeed. You want to do better than your colleagues, so if your colleagues are working 80 hours, you want to work 85.”

One of the key crunch points of frenetic activity happens during the seven years academic economists are working toward tenure, typically when they are between the ages of 28 and 35 — key child-rearing years for many women.

For many concerned observers, part of the solution to the gender gap in economics is to offer greater flexibility for women wanting to become tenured professors in economics, or economists in the public and private sectors.

In France, many institutions allow women to attain tenure as junior faculty — providing better pay and more security in those time-pressured years.

In the U.K., the system is less flexible but there is a push to introduce childcare vouchers and sabbaticals to help women better navigate the demands of academia and motherhood.

However, such initiatives remain in their infancy and are institution-led. There are calls among the institutions for state-led changes to maternity and paternity-leave policies to help improve the situation.

Fighting discrimination

In addition to these social challenges, there is evidence to suggest that the relatively few women who do manage to stay the course can face further systemic obstacles.

Economics remains a largely conservative profession, and suggestions of gender bias and even discrimination are rife.

Empirically testing for discrimination is difficult to prove due to the number of so-called “unobserved variables”, and most studies to date have been theoretical.

However, Heather Sarsons, a Ph.D. candidate in economics at Harvard University, has recently stoked the debate with her own research into how economists are being recruited by top U.S. universities over the last 40 years.

Using data extracted from CVs of academic economists, Sarsons examined whether co-authored and solo-authored publications matter differently for men and women in the attainment of tenure.

In her report, first published in December 2015, Sarsons concludes: “There is evidence that women suffer a ‘co-author penalty’. While women who solo-author everything have roughly the same chance of receiving tenure as a man, women who co-author most of their work have a significantly lower probability of receiving tenure.”

And so a picture begins to develop of a system working against women, even if unconsciously. The period in which economists are either promoted or fired, long referred to as a time of “publish or perish,” might need to be amended to “publish on your own or perish” if you are not a man.

It’s a worrying situation for an influential field that has far-reaching implications and helps shape government policies.

The problem is heightened once you consider that many women economists specialize in important areas of economics not so keenly explored by their male counterparts, such as family, labor and inequality.

Active industry initiatives

Professor Emmanuelle Auriol at the Toulouse School of Economics calls the loss of female economists between Ph.D. level and professor level “startling”.

“I have been doing this job for more than a quarter of a century, and when I started, I asked, ‘Why are there no senior women?’. I was assured, ‘Don’t worry, it will improve with time’ — but I have to say that, 25 years later, I do not see any clear improvement. I am concerned; there is something wrong here.”

Since the start of 2016, Auriol has been leading attempts to combat the problem head-on as Chair of the Women in Economics (WinE) Committee of the European Economics Committee.

Established in 2004 and re-imagined in 2010, the WinE Committee works closely with a similar initiative in the U.S., and aims to facilitate the formation of networks by circulating information on, or relevant to, female economists, and by providing a forum for discussion.

Among the WinE Committee’s initiatives has been the creation of the Birgit Grodal Award, presented every two years to a European-based female economist who has made a significant contribution to the profession.

The Birgit Grodal winners

In 2014, the Birgit Grodal Award was presented to University of Manchester’s Rachel Griffith, a leading empirical researcher in studies of innovation and productivity. Her influential contributions have brought new data sets, particularly business data, to help answer classic economic questions about what drives the process of innovation, and what determines differences in productivity levels between firms.

In 2012, the award went to Hélène Rey of London Business School for her pioneering contributions to the understanding of international finance. She demonstrated that looking at a country’s asset positions helps predict current-account adjustments and applied this insight to the case of the United States.

In addition to the awards, the WinE Committee runs an annual mentoring and networking retreat for young female economists.

“As Chair of the WinE Committee I try to be optimistic and these are positive initiatives,” says Auriol.

“We need to inspire and train women. The annual program for 50 junior faculty acts as a mentoring program with senior economists. It provides an important space for economists to talk about their papers, and also wider topics around succeeding and reconciling family and work commitments.”

Another important new initiative Auriol is driving this year focuses on the collection of information on the structure of economic departments within the European Union.

With support from the European Economic Committee, computer software is being installed on the Web pages of economics departments to better track applications received and processed by institutions of higher education.

For Auriol the motivation is clear: “It is very hard to push policy and convince people there is a problem if you do not have statistics and do not know exactly what is going on. As economists, we are well aware that you cannot change policy based on conviction alone.”

Signs of optimism

It is not just economics, of course, that has problems with gender parity. Within academia, men are tenured at significantly higher rates than women in most quantitative fields.

The year 2009, when Ostrom received her Nobel Prize, proved to be something of a high-water mark for recognition of women in the Nobel Prizes, with five laureates: Herta Müeller won the literature prize; Elizabeth Blackburn and Carol Greider were awarded in physiology and medicine respectively; and Ada Yonath in chemistry.

To place their achievements in context, Nobel Prizes have been awarded to women 49 times in its 115-year history, compared to 825 prizes awarded to men. (One much-celebrated woman, Marie Curie was honored twice, with the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics and the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.)

But progress is being made, encouraged by the Nobel Prize organization itself, which has started to actively highlight the number of women being recognized each year.

Since the start of the 21st century, 19 women have won a Nobel award — more than in the preceding 40 years combined — when 18 women were recognized between 1960—2000.

At the other end of the pipeline, the percentage of women in education studying science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) subjects is also increasing, thanks in part to a growing number of campaigns and events designed to drive awareness of potential career paths.

Women are reported to comprise 14 percent of the STEM workforce in the U.K., and around 24 percent in the U.S.

UBS’ Donovan notes that the gender imbalance is not going to be solved overnight, but he does see “signs of optimism”. He believes the concerted push to boost the numbers of women involved in mathematics should be positive for economics.

He adds: “We can and should be pushing for better equality. Within any monoculture — in terms of gender or ethnicity — you’ve got a problem. If you are excluding 50 percent of the population from serious analysis during a time of such profound change, then you’ve definitely got a problem.

“But, there have been a number of papers in recent years looking at why there are not more women in economics, and I think broader analysis around prejudice and discrimination is also becoming more mainstream.

“There is growing recognition that we need a diverse range of inputs into any kind of analysis.”

Turning a vicious circle into a virtuous one

One thing all the women that we spoke with had in common during their formative years was the lack of female role models. This inability to see other women gaining global recognition and achieving the highest accolades clearly exacerbates the leaky pipeline.

One woman helping to inspire others and expand the horizons for women in science in general is the quantum physicist, Gemma Godfrey.

The former Head of Investment Strategy at Brooks Macdonald, and Chair of the Investment Committee at Credo Capital, has become a regular and trusted media commentator, and now enjoys international recognition.

Godfrey made time while filming NBC’s “The Celebrity Apprentice” with Arnold Schwarzenegger and Warren Buffet to share her thoughts on what she calls a “self-perpetuating vicious circle” for women.

“It starts from a lack of awareness of the multitude of job opportunities these disciplines could create,” she says. “It’s then magnified by the dropout rate of women as they climb the career ladder, due to an absence of support or guidance.”

“There needs to be a greater understanding that the skills these subjects instill in students offer many career paths. Many financial institutions have networks to support women, but it is the involvement of key stakeholders, whether male or female, which drives its impact.”

Hope also comes from a cohort of senior trailblazers who are helping to create the climate for change.

Christine Lagarde’s rise to the top post of the International Monetary Fund is a notable achievement no woman has attained before.

The widespread support for Lagarde — a lawyer by training, not an economist — was underlined last month when she was elected to serve a second five-year term as Managing Director of the IMF, starting on July 5, 2016.

Elsewhere, Janet Yellen, the Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, has won global recognition for her ability to connect economic theory to everyday life.

Further inspiration can be found in the success of Claudia Goldin, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics at Harvard University and Director of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Development of the American Economy Program; and Anne Case, the Alexander Stewart 1886 Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, and a Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and the Economics Department at Princeton University.

For Godfrey, who is preparing to launch her own wealth management service, Moo.la, the presence of such high-profile women, is an invaluable part of addressing the problem.

“An effective support system consists of peers to relate to, mentors to guide, sponsors to champion and role models to inspire,” she says.

“They say it takes a village to raise a child and it can often take the same to shape a person's career. I know personally that I have a lot of people to thank for helping me get to where I am today.

“The most direct way to change any imbalance is to do it by virtue of your own career - getting the impact you want to see, rather than just talking about it. With more visible and audible role models, and a more equal support system, we can turn a vicious circle into a virtuous one, and attract and retain more women.”

Explore more about Elinor Ostrom in the UBS Nobel Perspectives series

Hear more from Paul Donovan UBS economics weekly podcast