Crafting to the Highest Standards

Alone among global luxury jewelers, Tiffany tells clients about every step of the journey—from earth to finger—of its newly sourced, individually registered diamonds. At every stage, there are artisans and craftspeople who embody the company’s values of sustainability and diversity. These are their stories.

Provenance

Responsible

Sourcing

Preparation

Designing

Tiffany True®

Cutting & Polishing

Building

Opportunity

Grading & Setting

Promoting

Women

The Client

The Diamond’s

Second Journey

Responsible Sourcing

Tiffany has a history of championing conservation and responsible mining stretching back 25 years—far longer and deeper than other jewelers.

Protecting the Wilderness

In 1995, Tiffany urged the U.S. Department of the Interior to prohibit construction of the New World gold mine that threatened Yellowstone National Park. The project was ultimately dropped. The experience made Tiffany realize the positive influence the company could have on the jewelry supply chain and the mining sector.

Funding Environmental and Social Change

In 2000, the Tiffany & Co. Foundation was established. In the two decades since, it has awarded more than $85 million in grants, with much of that funding going toward environmental organizations, including those advancing responsible mining.

Banning Blood Diamonds

In 2003, Tiffany led efforts to encourage the United States to implement the Kimberley Process. The Process prevents the sale of so-called blood diamonds, which are used by rebel groups to fund conflicts against governments.

While the Kimberley Process banned the diamond industry’s most egregious practice, it did nothing to address child labor, human rights or environmental violations. To go beyond the Kimberley Process, Tiffany began buying directly from mines it trusted and handling much of its own cutting and polishing.

“Tiffany & Co. has really stood out by saying, ‘We won’t buy diamonds associated with human rights violations or environmental degradation,’” says Payal Sampat, Mining Program Director for the nonprofit Earthworks.

Responsibly Sourcing Rubies

In 2003, Tiffany stopped sourcing rubies from Myanmar because of human rights violations and a lack of transparency in the ruby supply chain.

Defining the Best Mining Practices

In 2006, Tiffany became a founding member of the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA), which is composed of mining companies, labor groups, affected communities, nongovernmental organizations and companies that purchase mined materials.

After a decade of collaboration, in 2020, the first mines were audited to determine whether they met the robust social and environmental guidelines for responsible mining created by IRMA.

“Tiffany has done something that’s rare for companies—it’s addressed what responsible mining means far beyond just its own sourcing,” says IRMA Executive Director Aimee Boulanger. “And it’s gone from advocating for elimination of the worst practices to defining what are best practices in worker safety, biodiversity and the environment.”

Making Tiffany’s Sustainability Transparent

In 2015, Anisa Kamadoli Costa was promoted to become Tiffany’s first Chief Sustainability Officer. Four years earlier, she led the creation of Tiffany’s first sustainability report about its operations, diamond and metal sourcing and public stances on key issues—a milestone for transparency in the industry.

Disclosing Where Diamonds Come From

In 2019, Tiffany became the first global luxury jeweler to provide to clients the region or countries of origin of its newly sourced, individually registered diamonds. A year later, it started disclosing the locations for all steps in the craft journey of these diamonds.

Preserving Wild Salmon

In 2020, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers denied a permit for a gold and copper mine in Bristol Bay, Alaska, dealing the project a major blow. Tiffany and others have opposed the mine for more than a dozen years.

The mine would be located at the headwaters of one of the world’s greatest remaining wild salmon watersheds. The Army Corps found it was “contrary to the public interest.”

A Tiffany executive testified before Congress, the company took out newspaper ads opposing the mine, and raised awareness alongside diverse groups such as Alaskan natives, conservationists and the fishing industry.

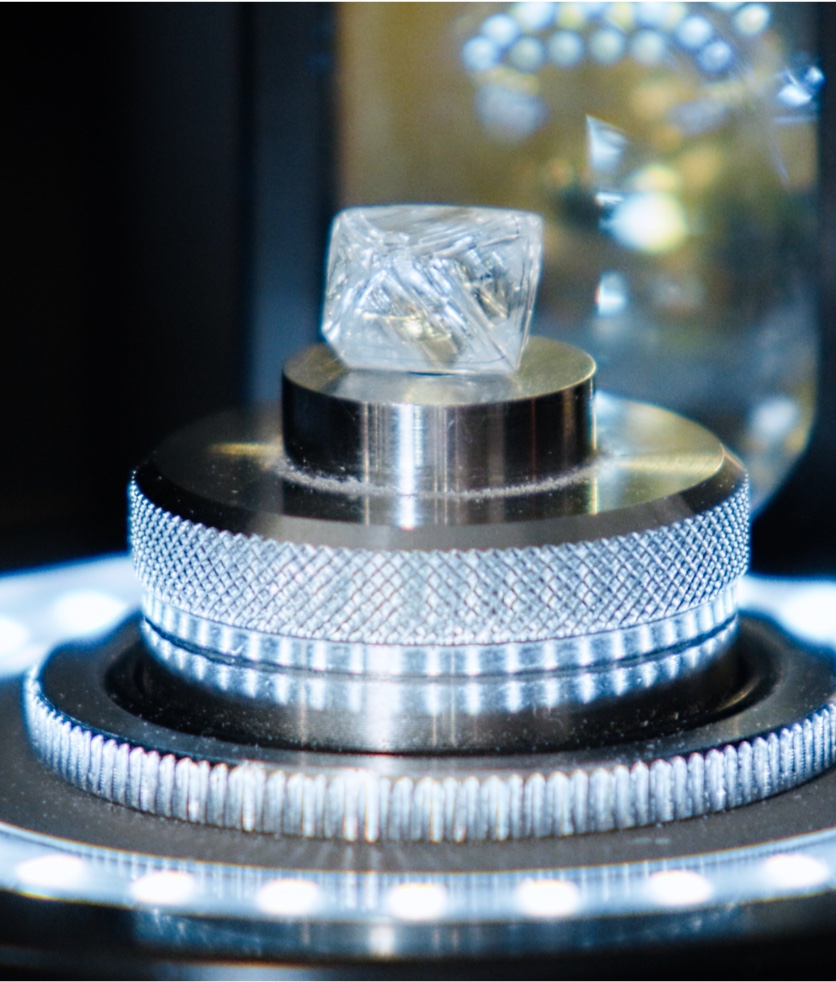

Designing Tiffany True®

A Cleaner Way to

Clean Diamonds

For generations, rough diamonds were washed in boiling acid—a dirty and dangerous procedure. Tiffany recently switched to a liquid salt solution, heated to 250 degrees F.

We’ve reduced the potential harm to employees and the planet.

Building Opportunity

Calculating a

Living Wage

Tiffany is a global pioneer in paying living wages in its workshops in developing countries, and has worked with independent researchers and experts for more than a decade to ensure that employees are paid fair wages based on the cost of living in each locale. In Tiffany’s Cambodia facility, pay is significantly higher than at typical local factories.

Employee benefits include a free doctor’s office on site, breakfast and lunch provided by the company and—unusual for factories in the tropical nation—air conditioning.

About one-third of electricity needs at the Cambodian facility, which employs 1,500 people, are derived from solar power generated on site.

Promoting Women

Just north of New York City in Westchester County, in an unmarked building, is Tiffany’s Gemological Laboratory—which grades diamonds and sets quality-control standards—and its workshop for high jewelry. Over 16 million diamonds pass through the building annually. Of the facility’s nine senior managers, seven are women.

For centuries, jewelry has been a man’s profession, but Tiffany is a female-majority company. Of its global workforce, approximately 70% are women, and about 60% of its managers and those filling senior positions are women.

Elsa Alberto runs the 66-person Westchester workshop. “You have to understand how the pieces we make will behave when they’re being worn,” she says. “Is the client going to be dancing or hugging someone? How can we assemble a piece to account for that? Both women and men can learn that skill.”

What Tiffany does is hire the best candidates for the job, regardless of gender. And that’s why women are climbing the ladder, because there are a lot of smart women out there. The times are changing.

Nelli Konchak moved to New York from the Soviet Union in 1990 at the age of 25, when she spoke “none, zero, zip” English. At another jewelry company where she first worked, “everybody was saying that Tiffany quality is like the best of the best. I thought: Why can’t I work there?” She joined 16 years ago, making the four-hour round-trip commute from her Brooklyn apartment to Westchester daily.

“For me, it was important to actually become someone,” she says. “When you have the ability to improve something in the company, especially at Tiffany, I think it’s amazing.” Today, she oversees planning, making sure Alberto’s craftspeople have the precious stones and metal they need to create each piece.

Laura Housel manages the 45-person Tiffany Gemological Laboratory, her third role since joining the company almost a decade ago. After the diamonds are cut and polished in other facilities, her team records their cut, color, clarity and carat weight, and determines whether they meet Tiffany’s standards. If they do, the team uses a laser to etch a tiny serial number onto each individually registered diamond, which identifies its entire craft journey.

I can see from the time that I started, Tiffany has really put inclusivity at the forefront of our culture. That makes a huge difference in how we lead.

In the end, because they are creating jewelry primarily for other women, the women of the Westchester facility have an emotional connection different than that of most men. “I’ve seen my grandma’s reaction to getting a Blue Box,” Housel says of Tiffany’s iconic packaging. “Seeing that moment and knowing that I am a part of creating something like that for so many millions of people—it is really magnificent.”

Inside Tiffany’s

Westchester Workshop

Much of Tiffany’s high jewelry, including pieces that grace nominees on red carpets, is produced in the Westchester workshop.

The Diamond’s Second Journey

Passing on Values

with Jewelry

When a diamond engagement ring is first slipped onto a finger, it’s the end of its first journey and the start of its second. Tiffany jewels become heirlooms, passed down from generation to generation.

That makes knowing how they were made all the more important, says Sonya Keshwani, who got engaged and married last year. “Knowing this ring helped to conserve places of great natural beauty and promote communities around the world makes me proud to wear it,” she says.

Every day it’s on your finger, you carry the values that went into making the ring. So will those you pass it down to.