Turning Point: The Space Opportunity

For a new generation of entrepreneurs, space isn't the final frontier. Instead, space is an increasingly crowded field of innovative startups and established players that are creating the most exciting companies of today and tomorrow. Learn about the new space race and meet two companies that are challenging the status quo with innovative technologies and a relentless spirit of discovery.

Spacetech entrepreneur Simon Gwozdz traces his lifelong fascination with space to watching Apollo-13 as a wide-eyed five-year-old – a film that sparked his obsession with going to the moon, and one he still rewatches when the going gets tough.

Twenty years later, Gwozdz’s lifelong obsession took on a new mission. As the co-founder and CEO of Singapore-headquartered rocket propulsion and space launch startup Equatorial Space Systems, Gwozdz and his team are building a patent-pending rocket fuel formulation that remains stable in flight – a necessity for commercially viable hybrid rocket launches, and a technologically challenging feat where most other companies have fallen short.

For Gwozdz, challenging the existing hegemony in rocket launch begins with changing the economics and risk profile of a fundamental part of every rocket: propulsion. “I think we actually stand a good chance if we don’t mess things up along the way,” says Gwozdz.

To make propulsion safer, more efficient and cost-effective, Equatorial Space Systems is creating innovative solid fuel formulations that blend liquid oxidizers with solid fuel. These formulations are inherently non-explosive, and can propel rockets at an estimated fraction of the cost of fully liquid systems. The launchers serve wide-ranging needs, from student training kits to low-earth missions carrying up to half a metric ton of cargo.

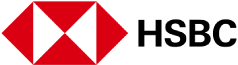

Equatorial Space Systems’ journey from a flight of fancy in 2017 to a pre-series A company in 2024 has not been an easy one. With a starting capital of $5,000, the startup was “as grassroots as it gets” and had to create its own opportunities.

“An important characteristic I'd recommend to anyone trying to get into entrepreneurship, especially involving hardware or deep tech, is to do what you can with what you’ve got, where you are – now. Don’t wait for the perfect opportunity, because it’s never going to happen,” Gwozdz says.

“Even if it’s a dumb-looking prototype that you put together with adventurous materials, it’s important to show you’re doing something real, something that actually exists beyond a Powerpoint.”

The very first miniature rocket model that the team assembled on portable tables outside a university hall was built on Gwozdz’s advice, and would eventually serve as a crucial springboard to Equatorial Space Systems’ first office: an on-campus incubation space at NUS Enterprise, the National University of Singapore’s entrepreneurial arm.

So too did this early space pave the way for subsequent fundraising. Most of Equatorial Space Systems’ investors, including its latest backers: Australia’s Northern Territory Labor government and Paspalis, first encountered the startup back in 2019, when visiting Singapore to explore the growing spacetech scene.

“It can be a long journey. It can take four, five years to develop a company and mature it to the point where investors will commit to you, but it’s important to make a start and build connections early,” notes Gwozdz.

After an active effort to reform the company and move away from what Gwozdz calls a geographically limited, frog-in-a-well mentality, 2019 marked a turning point in its international expansion.

“In this time and era, you realize it doesn’t matter if you’re sitting in the next office or the next country, or a completely different continent. You start changing your mindset from ‘everything has to happen under one roof’ to ‘people can live comfortably somewhere else and be brought in as and when needed.’”

With specialists in Argentina working on flight dynamics and structures, engineers in Thailand, a team in Singapore, and a few spread across Australia, the United States and France, Equatorial Space Systems is a decidedly global effort. “The sun never sets at Equatorial Space Systems,” Gwozdz says. “It takes an ecosystem to pull something like this off.”

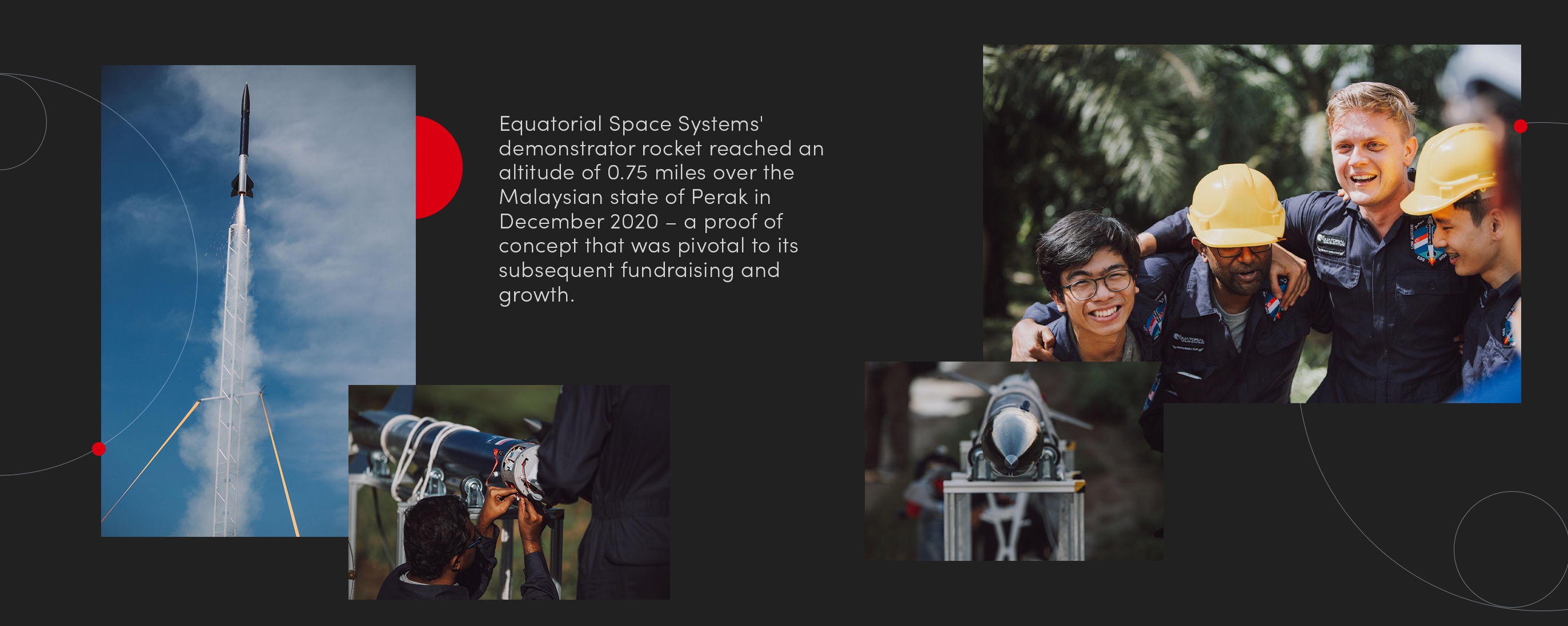

Equatorial Space Systems’ first big test came during the height of the pandemic in 2020 – the year the startup had nearly run out of money, and had to move from an office to a storage unit. To demonstrate that the core propulsion technology worked as advertised, co-founder Praveen Perumal pushed through with a low-altitude test flight. That led him to a mountain range in Perak, Malaysia.

In navigating unfamiliar terrain, Equatorial Space Systems found widespread support. The Malaysian state gave Equatorial Space Systems permission to use the land as a test site, while a Malaysian university helped make local arrangements, and a private company helped the team process crucial paperwork.

“We wouldn’t have known how to navigate all that. It goes to show how important it is to make friends and close connections and cherish them along your journey, because there will never be a situation where you know it all,” reflects Gwozdz.

Equatorial Space Systems will only consider itself a space company after a successful test flight in low earth orbit, slated for late 2024. But its earlier proof of concept in Malaysia has, in Gwozdz’s view, helped it cross the chasm from being a wantrepreneur to earning a seat at the space exploration table. This newfound, hard-earned credibility was crucial for Equatorial Space to secure further contracts and raise fresh venture capital.

“We went from talking about launching a hybrid rocket to actually launching one. Everything changes once you do what you say. We started to pop in the right circles,” says Gwozdz.

The successful test flight ushered in a series of early grants, angel investments and acceptance into three global accelerator programs, including the Techstars Los Angeles Accelerator 2022. It was this experience that Gwozdz credits with transforming a passion-driven ideal into a marketable game plan, from defensible intellectual property to thinking in terms of return-on-investment. But Equatorial Space Systems knows it will take many more years to build the company to the point of exit.

“Whether it’s an IPO or a SPAC, we’ll worry about going public when we get there. We’re focusing on becoming the gateway to changing the fundamental architecture of the launch vehicle,” says Gwozdz.

And for those questioning whether a space startup with unexpected origins can pull off such a mission, Gwozdz notes that space ambitions have never been confined to a single nation, continent or company.

“I think the adventurous spirit of humanity is universal. This is Exhibit A – we’re sitting in a country not historically associated with space, and we share the same ambitions: we want to have our mark and say in the future of space.”

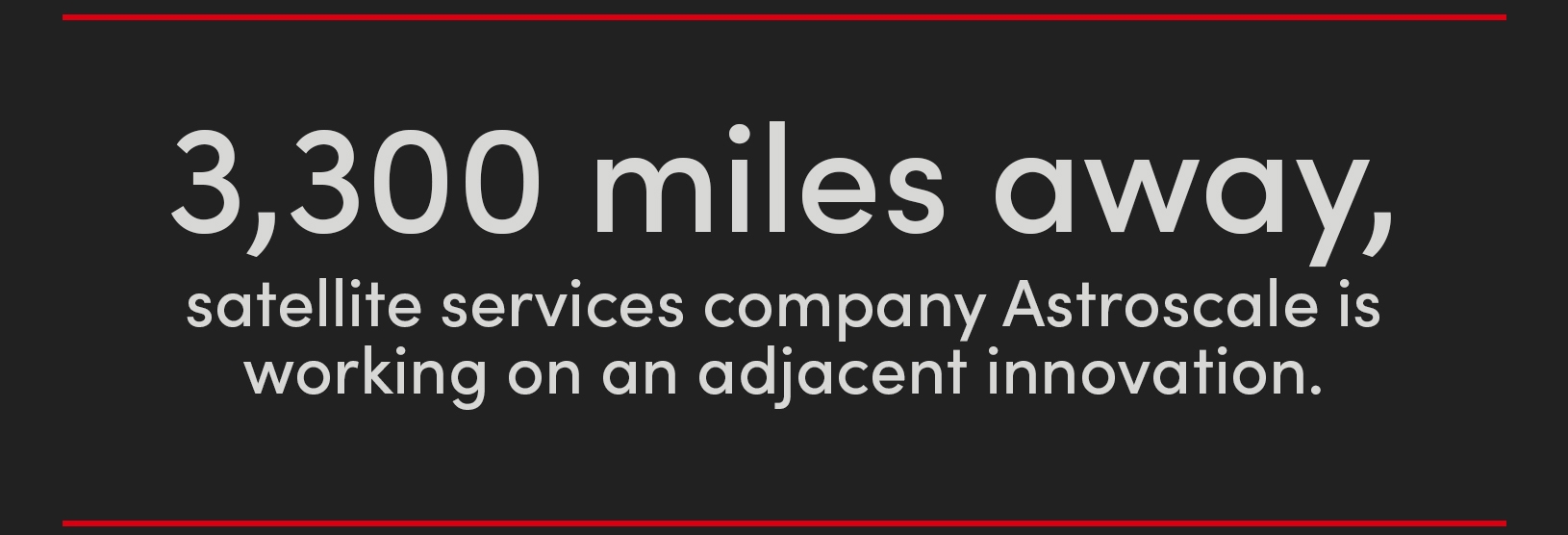

From a garage in northeastern Tokyo in 2015 to the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 2024, satellite services company Astroscale has shown that measured, step-by-step determination pays off.

To mitigate the hazardous buildup of large space debris, which now totals 36,500 pieces, McKinsey veteran Nobu Okada started an orbital debris removal company with $200,000 of personal savings in 2013. At the time, the commercial space sector was still nascent, and industry giants like Starlink had not yet entered the scene.

Despite early industry excitement around the possibility of space debris removal, fundamental questions remained. Who would be willing to pay? How was the regulatory environment going to work? The technology to approach, grab and transport an object in orbit is technologically complex – how were these immense problems going to be solved by a tiny team of fresh graduates and near-retirees?

When Astroscale moved its headquarters from Singapore to Tokyo in 2015, Okada invited Chris Blackerby, who was then NASA’s Attaché for Asia at the American Embassy in Tokyo, to raise a toast to the company.

“People might look at Astroscale and think it’s crazy. But the idea of going to the moon within eight years in 1962 was pretty crazy. The idea of building an international structure in space with dozens of countries bringing in capabilities is still crazy,” he said, while holding back a hint of skepticism. “Both of those things were done. If others share that vision and that support, it’s certainly possible.”

Two years later, Blackerby took his own leap of faith when leaving a secure government position for a fly-by-night startup “with 30 people and no revenue.” What convinced him of Astroscale’s long-term viability was the advent of large commercial satellite constellations like OneWeb.

Up till 2017, Astroscale’s customer base had mainly been governments looking to bring down their large objects. But as space exploration companies began to launch hundreds of thousands into low earth orbit, with an estimated 30% of them failing, Blackerby could see a surge in demand for satellite preparation and maintenance.

“And if they do fail, we’ll be the ones to pull them out of the way. Now I could see a more recurring capability for satellite removal: a combination of government and commercial demand.”

As the group commercial operating officer of Astroscale, Blackerby’s first order of business was internationalization. In 2017, Astroscale had about 20 people in its Tokyo office, and five in the Singapore office.

Okada and Blackerby quickly realized that the company was never going to survive if it was based in only one or two countries.

“The policies around satellite services and space development are global; the customers are global; the workforce is global. We recognized the need to have options, regardless of nationality,” Blackerby explains.

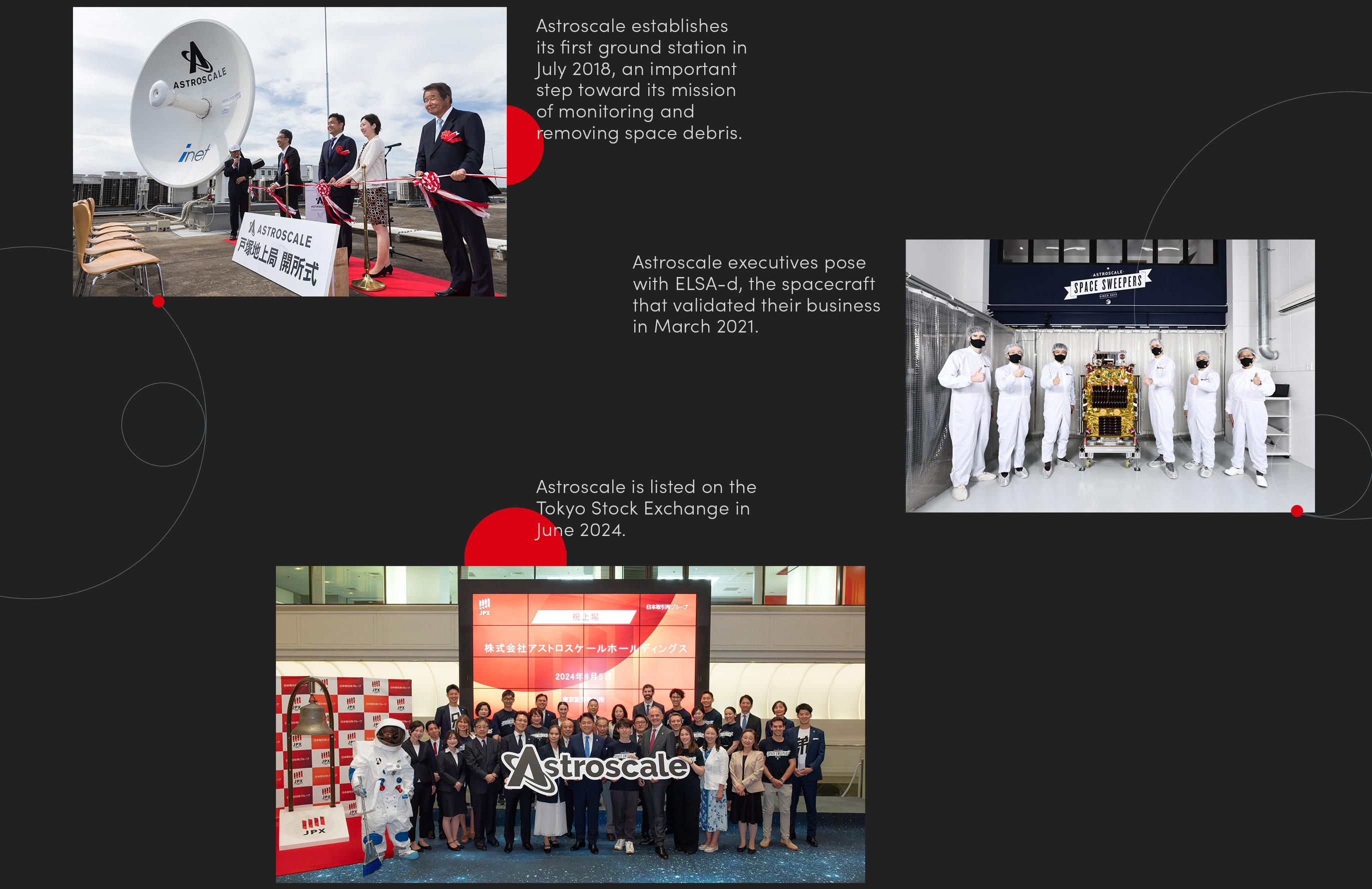

That global approach was a requisite for one of Astroscale’s most significant achievements: its milestone ELSA-d mission, which demonstrated the ability to separate and magnetically reconnect two satellites in orbit. For years, this had been the ultimate test for Astroscale. Now, it had proof that the docking and undocking of a client satellite and a service satellite was not only theoretically but practically possible.

But obtaining a launch license for ELSA-d was challenging. Without a propulsion system, the dummy client satellite was essentially a brick in space – and few countries were willing to take on the risk. After rejections from nine governments, Astroscale finally obtained a green light from the United Kingdom, who not only sponsored the launch license, but also gave Astroscale an early-stage grant to build its satellite operations capabilities.

The company’s further expansion into the United States granted it entry to the epicenter of spacetech, while an office in Israel extended Astroscale’s capabilities from low earth orbit to outer space, and its latest office in France helped it gain a foothold into the European Union.

Despite its global presence, Astroscale did not find it easy to get investors to put money behind vocal support.

“We went through seven rounds of funding: Series A to G,” Blackerby recalls. “In each round, we had a hit rate of under 10%. In 2022, we were really looking to accelerate, but instead we went through a dry period in the post-SPAC boom.”

Astroscale’s ability to stay the course – and explain its satellite servicing opportunity more clearly with each round of funding – has paid off.

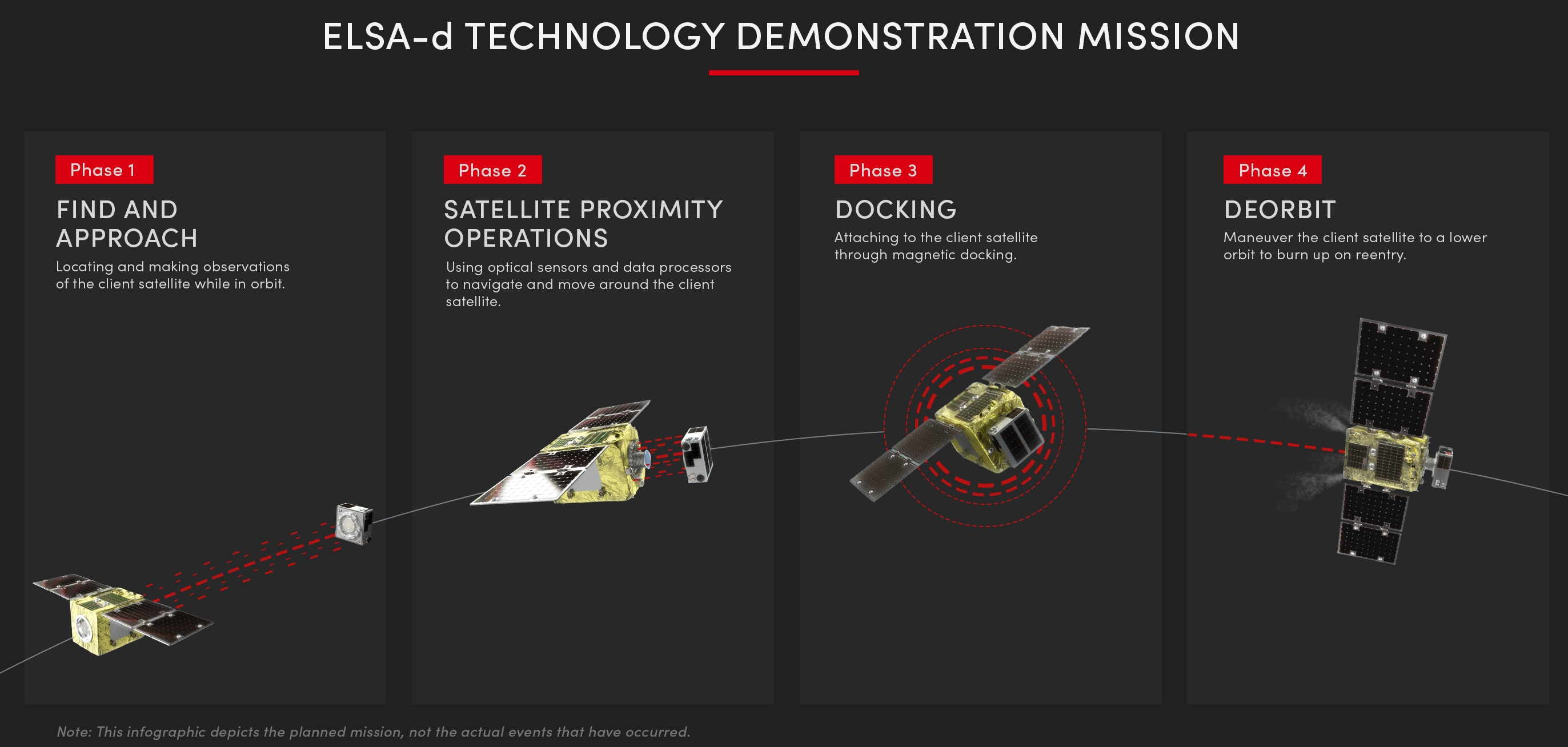

Following two missions in orbit over the last three years, Astroscale has developed new capabilities in building a supply chain, understanding what customers want from satellite servicing, and solving problems in orbit in real time. The world’s first close-up image of space debris, taken by Astroscale’s ADRAS-J spacecraft in April 2024, proved the value of its technology. “It elicited such a response in how close we got to an object in orbit,” Blackerby recalls.

For Astroscale, the path ahead extends beyond debris removal, and includes refueling, repairing, transporting and extending the life of a satellite. “It’s all based on the capability to identify, approach, rendezvous and dock with a satellite. If we can do all of those other things, the aperture opens way up,” notes Blackerby.

Following a breakthrough initial public offering on June 5, 2024, which saw the satellite services company raise 17.6 billion yen ($113 million) in fresh capital, Astroscale’s next step is approaching and capturing objects in space, beyond a series of successful inspections.

“If we look forward five to ten years, we’re going to see something unrecognizable. Services from orbit from the moon are going to be commonplace for our children. There’s going to be trash removal, deliveries and hotels in space. There’s never been a time with this much activity, where all these seemingly outlandish dreams are on the cusp of becoming reality,” says Blackerby.