Turning Point: The Startup Opportunity

In 2018, only a handful of companies around the world were working on cultivated meat – meat produced from cells cultivated in a lab instead of livestock grown on a farm, and focusing their efforts on beef and chicken. For former architect Carrie Chan, whose diet fueled a curiosity for alternative, animal-free proteins, the combination of a proven cell-based technology, the region's vast appetite for protein, and the chance to be a first mover in the Asia's alternative seafood sector was too good to pass up.

But wanting to shape the future of food wasn’t enough. Chan lacked a background in biotechnology, and knew her first priority was finding a co-founder who could fill in the gaps.

“In the fintech world, or in software and app-based startups, there are quite a few founder matching programs. Unfortunately, scientists generally don't hang out at this kind of beer-drinking social event. I needed another way to get leads, so I posted the role on job boards,” says Carrie.

Fortuitously, Carrie had met a scientific advisor at the first Good Food Institute conference in Berkeley in 2018. After shortlisting a few candidates, she asked her advisor to conduct technical interviews – and was able to recruit biotech researcher Dr. Mario Chin as a co-founder within two months.

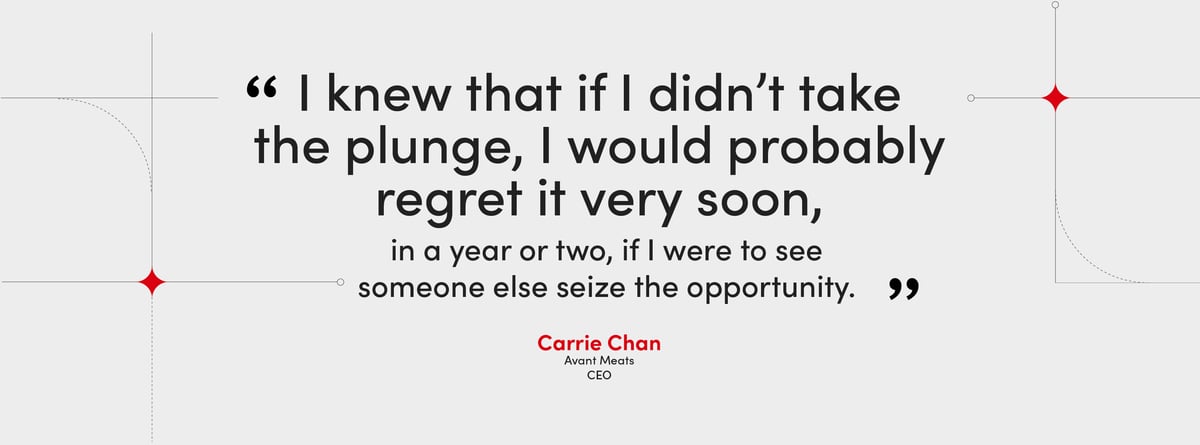

The early days were daunting for Avant Meats. With no patent, no cell line and no intellectual property to begin with, the startup's first step was figuring out what kind of fish product it wanted to work on. And it needed to find an R&D laboratory. "Some kinds of tech startups can start life in a garage, right? But a laboratory cannot be in a garage or a kitchen,” notes Chan.

From its earliest laboratory space in Hong Kong Science Park in April 2019, Avant Meats developed its first prototype, fish maw, within nine months. Its second prototype, fish filet, now costs around $5 per piece, down from $10 to $15 in 2022 – a testament to the progressive ramping up of R&D, and graduation from petri dish research to full-scale bioreactors.

The next turning point for Avant Meats was an unexpected one. An investor who eventually did not invest in the startup pointed it in a crucial direction: while he liked the business plan and the team, he advised Chan to expand her horizons and dip her toes into the global foodtech ecosystem.

Drawn to Singapore's "30 by 30" plan to scale up its agrifood capacity, Avant Meats embarked on a two-year partnership with Singapore’s A*STAR Bioprocessing Technology Institute. Right away, this opened doors to workflow improvements, otherwise cost-prohibitive equipment and a network of biotech entrepreneurs.

The partnership with A*STAR further laid the foundation for Avant Meats to move from research and development to the next stage of its journey: food production. But building a new production facility in Singapore – a precursor to raising Series A – was a fraught numbers game.

“One of the challenges that may be less obvious from the outside is that a lot of the technologies in our industry are related to pharmaceuticals, but drug and vaccine developers often don't have the same cost sensitivity,” notes Chan. “So when we worked with a consultant to design and produce a cost estimate for the pilot plants, everything was really high-spec and expensive. We got a set of numbers well beyond what we could afford."

This prompted Avant Meats to restrategize. By laying down assumptions more suited for a food production company than a pharmaceutical company, the startup was able to slash its projected fit-out cost in half. “I think our cost reduction is significant because a lot of investors, and the public at large, have the impression that the capex for each of these factories is so expensive that the alternative protein industry is not going to be profitable in the long term. We can only prove that wrong by building something functional at a very reasonable cost,” says Chan.

As Avant Meats uses its pilot plant in Singapore to build a replicable blueprint of a cultivated meat production facility, from returns on investment to the number of employees needed, global partnerships and the scaling up of production are in the works. “It’s taken about twenty nos to get to a yes, and many yeses to reach this point. Some of those nos along the way have turned out to be a nice way of telling us we need to change our course of action.”

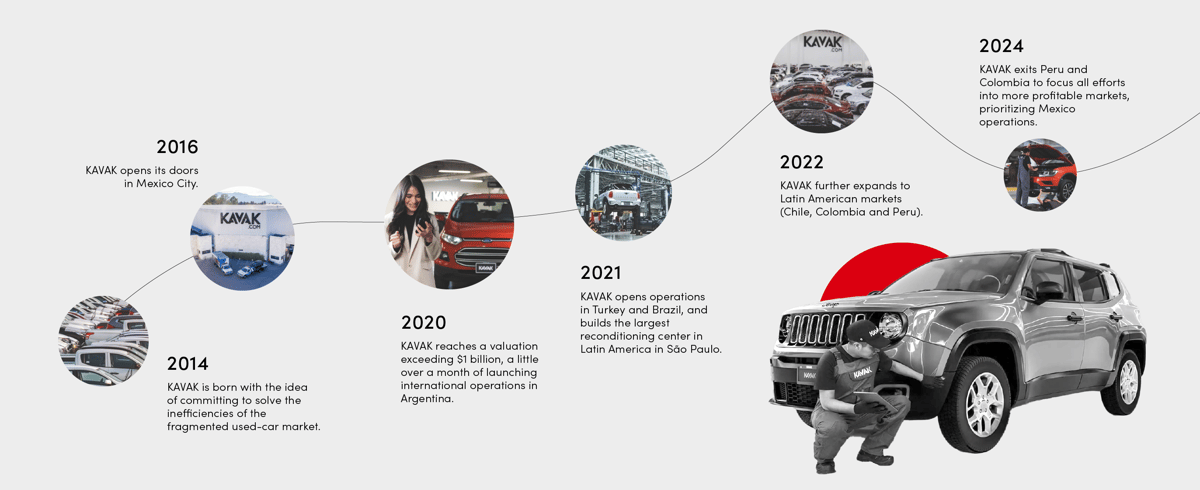

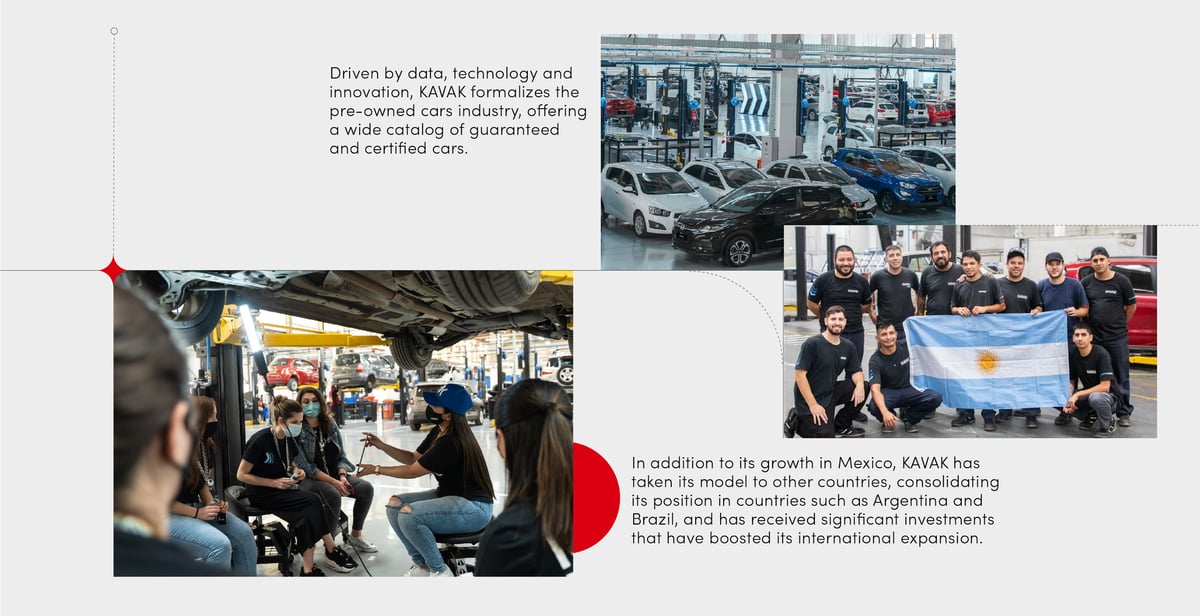

Co-founder Carlos García Ottati’s firsthand experience of being defrauded – once through vanishing payments when selling his car in Colombia, and again through forged documents when buying a car in Mexico – drove the Venezuelan digital marketplace veteran to create his own solution for Latin America’s secondhand car market, where an estimated 90% of car transactions take place in informal settings, and only 1 in 20 receives financing, compared to 9 in 10 in the United States.

For Ottati, this meant the key challenge in raising early capital was not getting investors on board with KAVAK, but getting them on board with Latin America.

“There was a lot of explaining to do about how building a startup in Latin America looks very different from building one in Silicon Valley. In Silicon Valley, founders are building that extra block that a product needs. Here, you're building the entire block. We needed to explain the underlying, systematic issues of the Latin American market,” says Ottati.

“We wanted to build an Amazon for used cars, but there was no Stripe, so we had to build our own payment solution. There was no FedEx or DHL, so we had to build our own warehouses, and our own network of drivers and trucks to safely deliver cars in a very unsafe environment. Whenever we go out for fundraising, we're ambassadors of the region first, and ambassadors of our company second," he continues.

From a foundation of mobile-first car services, spanning financing and logistics to maintenance and repair, the business scaled an “unimaginable” 35 times in 2020. KAVAK soon needed capital to support its rapidly growing financing business, which took off during the pandemic.

That’s when KAVAK started talking with HSBC. "They were the first bank to really understand the problem we were solving, and to see an opportunity to formalize the secondhand car market by helping people gain mobility, as well as access to efficient finance," recalls Ottati.

That same year, KAVAK expanded from Mexico City to Buenos Aires by merging with Argentine startup Checkars, a company it greatly admired. For Ottati, entering Argentina was a test to prove that KAVAK’s business model could work even in an environment with 20 to 40% depreciation on a monthly basis. Successfully doing so gave the team the confidence to continue expanding in emerging markets.

A little over a month of launching operations in Argentina, a fresh round of funding tipped KAVAK’s valuation past $1.15 billion.

At that point in time, KAVAK did not even know what a unicorn was, but their achievement marked a huge milestone for the ecosystem. "It was a nod to founders everywhere, but for us internally, it just elevated our stakes and our commitment to keep building. But there wasn't a party; there wasn't even an internal email. The mindset was more: we're getting this huge recognition externally and we need to live up to it. We need to work because we're just a four-year-old company,” reflects Ottati.

As a veteran startup founder, Ottati is realistic about the challenges of the entrepreneurial journey. “There's no way that you can build without making mistakes. From a macro perspective, you need to make more right decisions than wrong ones, but you have to embrace the obstacles. The obstacles become the journey – I think that's part of the game.”

The pausing of operations in Peru and Colombia in the beginning of 2024 highlighted how swiftly that game sometimes changes, and how even market leaders need to be prepared to pivot. Despite gaining the lion’s share of those markets within one and a half years, KAVAK knew it had to shift gears. “At the end of it, it was a matter of focus. We were selling more cars in Mexico by noon than we did in both of these markets combined in a month.”

That realization has given KAVAK the ability to refocus on markets like the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a more luxury-driven market than the emerging markets in KAVAK’s traditional portfolio – with distinct opportunities. “What we love about the UAE is that the governments are the entrepreneurs. A place that was just desert is now a city. I’ve seen how quickly things take off in this market. That's a dream because in Latin America, there’s a lot of legacy and informality that we have to build on top of. In the Middle East, we have a clean slate and can solve problems before they happen.”

Whether back home or afar, KAVAK has partners who understand its challenges. “The great thing about HSBC is that they’ve been more than just a financial partner. They’ve been a building partner, connecting us with people and introducing us to a lot of the businesses and initiatives that we're working with right now,” says Ottati. “I've been able to talk to the CEO of HSBC Mexico, for example, about everything that's going on, and he puts me in touch with people who understand our challenges. That's important for us, because we are so tunnel-visioned into KAVAK."

With 40% of KAVAK’s customers buying a car for the first time and half going on to double their income in 18 months, KAVAK’s vision of providing the mobility for people to improve their lives is in the fast lane.