Turning Article 6 into Reality:

The Japanese Mechanism Providing a Roadmap for Future Climate Investment

After six years of negotiations, a crucial piece of the climate action puzzle is in place.

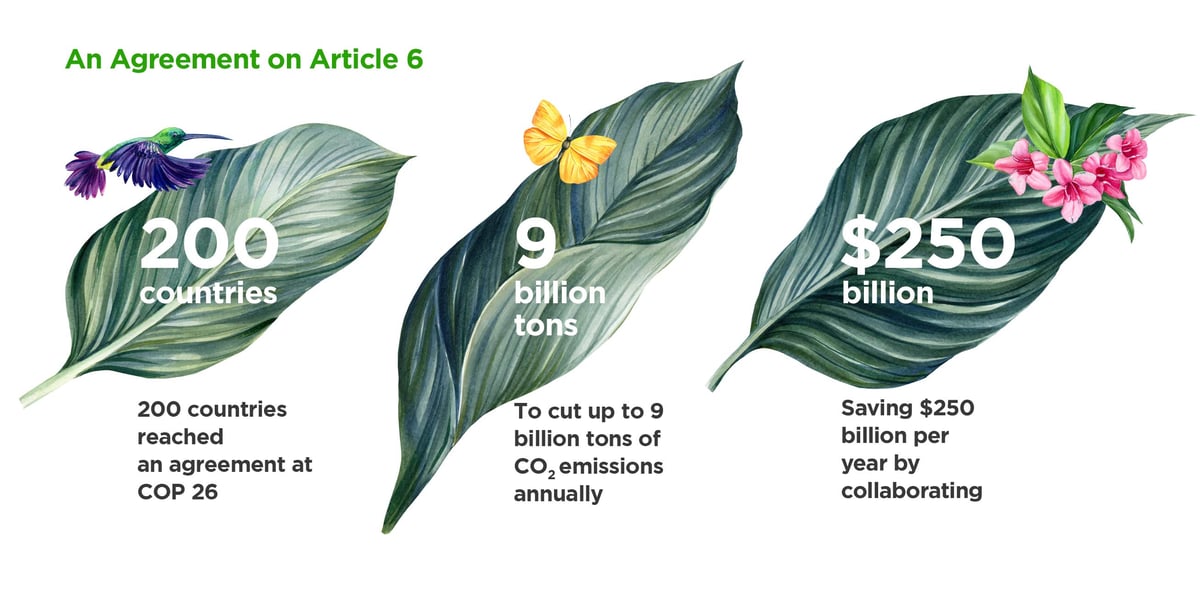

When 200 countries reached an agreement on the creation of an international market mechanism for trading greenhouse gas emission reductions at the recent COP26 summit, the last obstacle holding back implementation of a Paris Agreement rulebook was dismantled.

The agreement should trigger the release of billions of dollars in carbon-reducing investment, enabling the world to cut CO2 emissions by up to 9 billion tons and save up to $250 billion a year by 2030, according to the International Emissions Trading Association.[1]

The question of how these markets will work in reality is another matter.

Before COP26, the ad hoc nature of voluntary offset markets had been coming under increasing scrutiny. The passage of Article 6 offers an important opportunity for a reset, and for that the world will be looking for role models.

What is Emissions Trading?

Carbon markets and emissions trading are complex concepts.

Each country sets an emissions-reduction target under its national climate plan. This target is known as a “national determined contribution” (NDC). Countries that are unable to meet their reduction targets, or want to reduce the cost of meeting them, can buy emissions cuts from other countries, typically those that have already surpassed their targets, or expect to surpass them.

Emissions trading contributes to global decarbonization by enabling countries to take account for their own NDCs when they contribute to the reduction of emissions in other countries. This creates incentives for developed countries, especially those with advanced decarbonization technologies, to invest in decarbonization in developing countries.

There are two principal types of trading.

The first (Article 6.2) provides an accounting framework for international cooperation, such as linking the emissions-trading schemes of two or more countries.[2] It also allows for the international transfer of carbon credits between countries.

The second (Article 6.4) establishes a central UN mechanism to trade carbon credits from emissions reductions generated through specific projects. For example, Country A could pay for Country B to build a wind farm instead of a coal plant. Emissions are reduced, Country B benefits from the clean energy and Country A gets credit for the reductions.[3]

During the discussions, negotiators agreed to adopt Japan’s proposal to allow only credits authorized by the host country implementing a project under Article 6.4 to be used in NDCs, helping to address the problem of double-counting where two different parties claim the same carbon removal or reduction credit. Japan’s experience with its own Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM) ultimately proved persuasive.

The JCM: Promoting Simultaneous De-Carbonisation and Sustainable Development

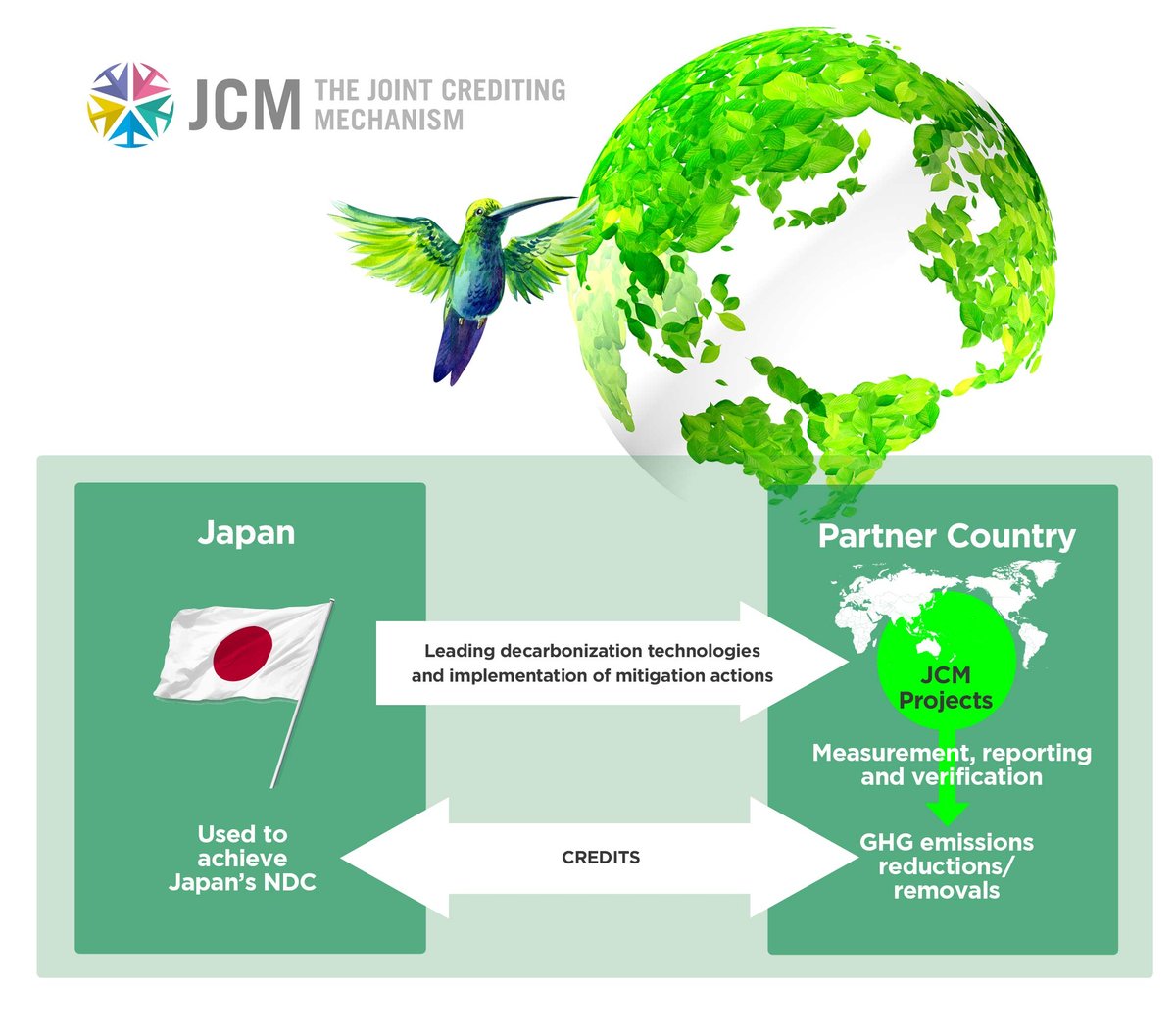

The JCM is a pioneering scheme based on Article 6.2 that has received considerable attention in recent years, setting an example that the Asian Development Bank described as “facilitating the diffusion of advanced decarbonizing technologies, products, systems, services and infrastructure as well as implementing mitigation actions, and contributing to the sustainable development of developing countries.”[4]

The JCM was developed in recognition of the necessity for all countries to commit to de-carbonisation. It addresses one of the primary challenges that many developing countries face: advanced decarbonizing technologies often have high upfront costs. Under the JCM, the Japanese government covers part of the initial investment. The subsequent emissions reductions or removals are then “quantitatively evaluated by applying measurement, reporting and verification methodologies”[5] and counted towards reduction targets.

By December 2021, 17 countries were participating in the JCM and over 200 projects were registered, such as the installation of high-efficiency water pumps in Da Nang, Vietnam, and high-efficiency looms at a weaving factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Japan aims to secure accumulated emission reductions and removals at the level of approximately 100 million t-CO2 by fiscal year 2030.

The JCM in Action: Spearheading Projects to Solve Multiple Challenges at Once

In Mongolia, for example, a joint venture between Japanese company Farmdo and Mongolian firm Everyday Farm LLC[6] has developed a Solar Farm® in the suburbs of the capital Ulaanbaatar with the combined goal of reducing air pollution and improving food self-sufficiency.

Farmdo first started operating its full-scale agricultural solar power systems that combine agriculture and renewable energy in Japan.

The business model reduces greenhouse gas emissions, promotes local production for local consumption through the supply of electricity from renewable energy and growing agricultural products. Leveraging the JCM, Farmdo brought its business model to Mongolia.

“The advantages of using JCM are the firm contracts between the two governments and the subsidies for capital investment. In the case of solar farms, JCM greatly contributes to reducing the overall capital investment. From a shareholder's point of view, receiving subsidies for business investments made in foreign countries provides great support for challenging businesses such as Solar Farm.”

As well as selling produce, the farm sells energy to the national grid. Since beginning operations, the farm has produced more than 60 million kilowatt hours of electricity as of end-2020.[7]

The project has been recognized by the Mongolian government as an innovative solution and received numerous awards, including the Green Certificate,the Silk Road Award, and Polaris Medal. Under the project, credits equivalent to 44,299 tons of carbon dioxide have been issued as of end-2020.

“Implementing a solar power project in Mongolia requires a large investment but through JCM we were able to receive partial subsidies from the Japanese government for our initial investment, which enabled us to install a large-scale solar power generation facility,” Jigjid Rentsendoo, CEO of Everyday Farm LLC in Mongolia said.

“The income from the sale of electricity from solar power has helped us introduce the latest Japanese agricultural technology and provide stable employment for our employees.”

Projects such as Everyday Farm offer an innovative vision of how the world can work in partnership to further the goal of tackling climate change. The agreement on Article 6 promises to make global collaboration like this more common, accelerating investment in climate-friendly technologies and making emissions reduction targets achievable.

At this key moment in history, Japan’s JCM is laying a path for the rest of the world, pointing the way towards a future in which economic development can go hand-in-hand with responsible environmental stewardship.