Walk the Talk to Green: Finance, Innovation, and Sustainability from Japan

In 2020, Japan vowed to cut greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. This declaration increased awareness of climate change and decarbonization in the private sector and catalyzed ESG investments. Combined with the government’s 14-sector Green Growth Strategy, Japan’s commitment to net zero accelerated innovation in decarbonization technologies. Today, innovation is booming.

Many of those innovations play a vital role in developing countries, accelerating their transition to cleaner and more sustainable forms of energy. To learn more about Japan’s drive to net zero and commitment to help other countries, we spoke with Mari Yoshitaka, Principal Sustainability Strategist at Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting Co. Ltd and Shohei Hara, Director General of Private Sector Partnership and Finance Department at Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

Changing Mindsets in the Private Sector

Q: We would like to begin by asking about ESG investments. Japan leads the world in participation in Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). Awareness around ESG appears to be growing in the private sector. What factors underlie that change?

Yoshitaka: The declaration of carbon neutrality for 2050 last year was a major factor. This changed the collective mindset in Japan. Awareness of ESG in the private sector has been growing in recent years, but last year's declaration around carbon neutrality proved a catalyst for further action. For example, Hitachi Ltd. announced its plan to achieve carbon neutrality across the entire value chain by fiscal 2050, in addition to its goal of eliminating CO2 emissions from its offices and factories by fiscal 2030. The company is building growth strategies around that to attract ESG investors.

The Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) spurred this trend. In 2015, GPIF became a signatory to the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI). And earlier this year, the Tokyo Stock Exchange revised its Corporate Governance Code to ensure that when restructuring the Tokyo Stock Market in 2022, the firms chosen for the First Section of the exchange are required to have commitment to TCFD.

Q: Is investment in sustainable assets and companies focused on decarbonization technologies also increasing?

Yoshitaka: The amount of funds invested in carbon-neutral-related stocks is increasing, spurred by the emergence of a “decarbonization sector.” Investors are interested in renewable energy companies, biofuel makers and electric vehicle-related names. In addition, green bonds—debt issued to raise funds for innovations that reduce carbon emissions—are quite popular among investors. Such bonds sell out instantly at the time of issuance. The amount of those investments, called transition finance, have been significantly increasing.

Investor Challenges and the Green Growth Strategy

Q: What is the state of funding decarbonization innovations in Japan?

Yoshitaka: It is difficult for financial institutions and asset managers to understand and assess the future valuation of technologies that do not yet exist. That creates a hurdle for financing and investment toward innovation. Investors need to train experts who can analyze innovation in this sector.

Q: Japan’s Green Growth Strategy focuses on 14 sectors. How does that help?

Yoshitaka: Both the Green Growth Strategy and the government’s Green Innovation Fund help investors get clearer picture of where their money will be allocated, encouraging more investments. With that, the pace of innovation will accelerate. For example, expectations are high for Japan to come up with innovation in the field of hydrogen and ammonia, taking advantage of its leading technologies in the sector. Meanwhile, investor appetite is growing in the building and mobility sectors as they relate to environmentally friendly infrastructure. In addition, Japan is quite competitive in energy management system (EMS) – both for homes and buildings.

Public Sector Participation and the Formation of Local Markets

Q: The trend of fund flows into innovation and clean energy in developed markets is growing, but this will have to contribute to decarbonization in developing nations in order to achieve carbon neutrality globally. With regard to this theme, JICA has been investing in and financing innovation to address climate change. Please explain the importance of JICA’s role.

Hara: Risks involving investments for renewable energy development and measures for climate change in developing countries remain high, discouraging investment by the private sector. Therefore, public organizations like JICA should take part in projects in these areas. The size of our individual financial inputs either in the form of loans or equities may not be significantly large, but we can contribute to the creation of new markets by showcasing what we have been doing in developing countries where demand for climate-change-related businesses is very strong. And that may encourage more organizations and private companies to participate in the future as they recognize the business potentials and viabilities. With an increasing number of climate-related projects being and to be supported by JICA, hopefully this area of investment and finance becomes a mainstream trend among private sector organizations.

Q: What are good examples of JICA’s investments and loans in this sector?

Hara: JICA financed a project company called Clean Energy Asia along with other international development finance institutions to develop the Tsetsii Wind Farm Project in the Gobi Desert. The farm began operating in October 2017. Overall, it consists of 25 giant wind turbines that can generate 50 megawatts of power—enough to cover around 5% of Mongolia’s energy requirements.

Another example is in Vietnam, we provided a loan for an onshore wind power generation project in Quang Tri Province in Vietnam, in collaboration with Renova Inc., Japan’s leading renewable energy and Independent Power Producer (IPP) developer, making this their first project in the country. Also in Vietnam and through the Leading Asia’s Private Infrastructure Fund (LEAP) with the Asian Development Bank, we contributed to finance the country’s first large-scale floating solar power plant. Solar panels were installed on the surface of the Da Mi hydroelectric power station reservoir in Binh Thuan. The plant has a peak capacity of 47.5 megawatts and will help reduce the country’s reliance on fossil fuels.

JICA also holds business contests in developing nations under Project Ninja. This project provides a platform for entrepreneurship support, with the aim of fostering entrepreneurs who can solve social issues as businesses and create high-quality jobs to assist nation-building in developing countries.

Meeting the Needs of Developing Countries

Q: What technologies do developing nations want from Japan?

Hara: Energy transition technology is required to realize carbon neutrality. Power supply systems in developing nations are generally weak, thus it is necessary to set up a solid transmission and distribution grid when installing renewable energy technologies that face intermittency challenges. That means EMS technologies are important.

Developing nations also seek access to Japan’s adaptation front, such like advanced weather forecasting technologies, as well as solutions for water leakage prevention, drainage systems, and disaster prevention. In Bangkok, where floods are common, JICA helped pilot project of a plastic rainwater storage structure developed by Chichibu Chemical Co. Ltd., a Japanese SME, for water management and the prevention flood damage. This resulted in purchase orders from the metropolitan government of Bangkok. Another thing to note here is that maintaining local employment at the same time of process toward carbon neutrality is very important.

Q: Where are investor interests with regard to decarbonization technologies in developing countries?

Yoshitaka: Investors are interested in how to trigger the energy transition. Decarbonization equates to disaster prevention. Japan is very competitive in distributed renewable energy systems, which is helpful for disaster prevention. Developing nations need distributed system as they don’t have solid electricity distribution structures. The other area is the hydrogen value chain, where Japan will be able to build infrastructure with developing nations. Some ESG investors may be interested in participating in such projects. Basically, investors are interested in infrastructure projects and distributed energy systems that lead to employment in local markets and foster sustainable businesses.

Hara: Indeed, there is good demand for grid management that cope with local conditions. For example, JICA is going to help feasibility study of installation of the EMS structure developed by Kyudenko Corporation in an island in Indonesia to cope with such issues. JICA also provided financing for Challenergy Inc.’s entry to Madagascar. This start-up developed the Magnus Vertical Axis Wind Turbine in order to overcome vulnerability of traditional wind turbines caused by typhoons and hurricanes.

Working Together to Achieve Decarbonization Around the World

Q: What is Japan’s strength in this area?

Yoshitaka: Japan has relatively advanced technologies, with the largest number of patent applications for clean energy and climate change globally. The question is how to take advantage of this to lead to the creation of businesses and markets. One important thing to note is Japan’s strong ability in co-creation—creating value with stakeholders. Decarbonization cannot be done without that. In other words, collaboration between competitors or among companies beyond the industry is necessary in order to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions. For developing countries, I believe Japan will be able to work with them to create carbon-neutral technologies that will take root and generate future growth.

Hara: Yes, the word co-creation really fits into what JICA has been doing, working together with developing nations and especially people on the ground. Collaboration is vital to overcome challenges around climate change and the energy transition. This is one of Japan’s many strengths. Japan’s collaborative mindset, long standing field-level presence, and accumulated trust with local partners enable us to help developing countries decarbonize through our technologies, investments and human resources much wider stream of collaboration for a better future.

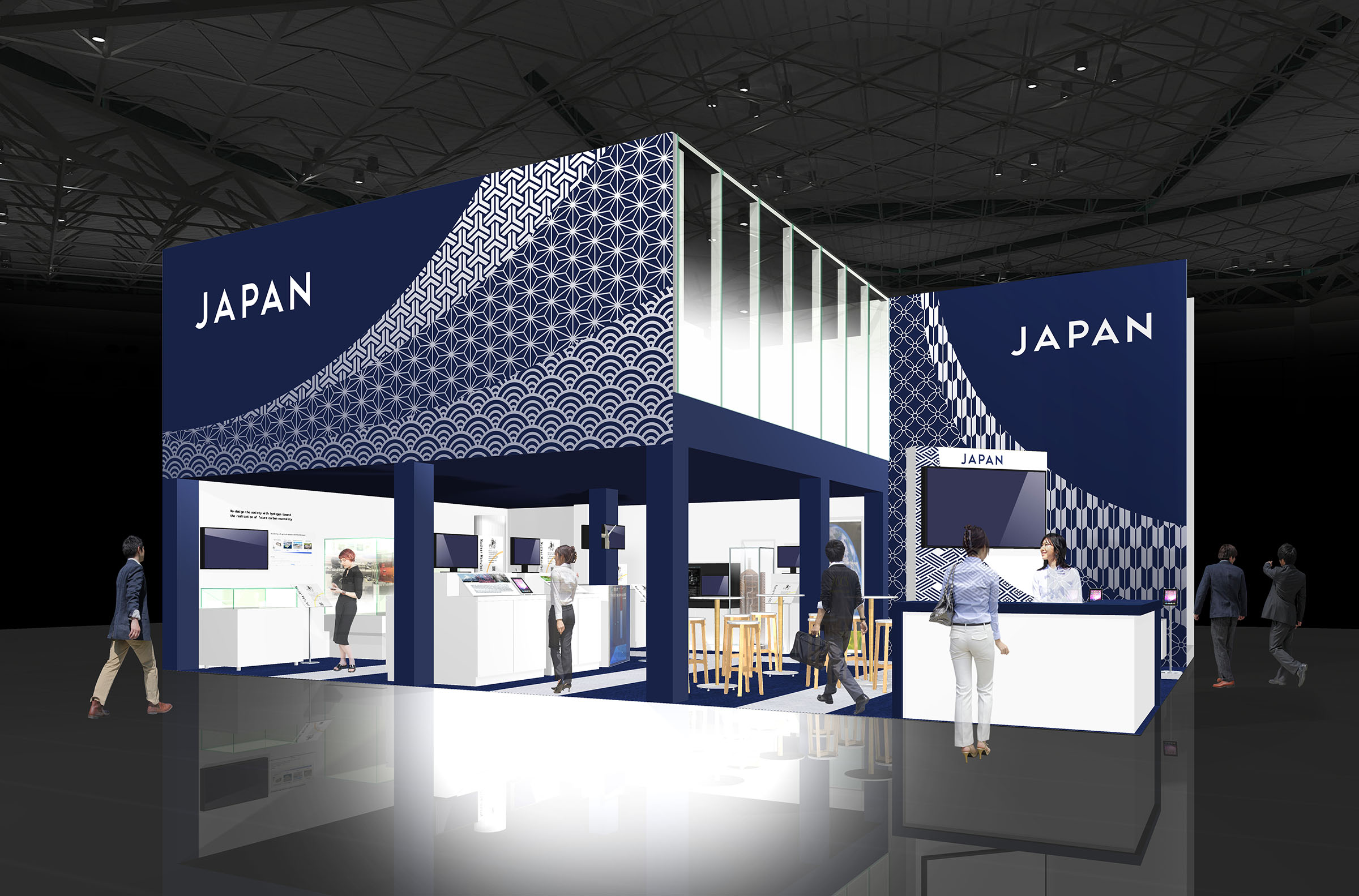

Learn more at the Japan Pavilion

For more information about Japan’s technology and supports for developing nations, see Japan Pavilion here.

All information in this article is based on the interview with Mari Yoshitaka, Principal Sustainability Strategist at Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting Co. Ltd and Shohei Hara, Director General of Private Sector Partnership and Finance Department at Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).